Around 1,200 shipping companies are registered in Greece. With overall 200,000 jobs related to the maritime industry, it is a major driver for the economy. Orestis Schinas gives an overview about Greek shipping, some reasons for its growth and which challenges lie ahead

Although Greek shipping enjoys a dominant position in the global market, as it corresponds to almost 18% of the global[ds_preview] fleet, and is constantly in the spotlight as well as attracts the interest of many journalists and analysts, it seems that there are still many myths about it. Therefore, a quick glance and cursory examination of some facts and figures related to the Greek shipping is given below, aiming to demystify some of the misconceptions.

A common misapprehension is the association of the Greek shipping with the dire financial standing of the national economy of Greece. In reality, the Greek shipping industry is a major contributor to the state accounts and its importance is also acknowledged from the government. Recently, the Minister of Mercantile Marine, Miltiadis Varvitsiotis, reported that Greek shipping contributes directly 7.6 bill. € in the national economy, i.e. almost 3.5 % of the GDP. Out of this contribution, almost 85 % is provided by deep sea shipping activity. The same source reports that the sum of 2.4 bill. € (~1.1 % of the GDP) is contributed by the shipping services industry and 3.4 bill. € (~1.6 % of the GDP) is measured as »magnifier effect« and indirect benefits. The figures suggest that almost 13.4 bill. € or 6.2% of the GDP (2012) is given back from the shipping industry to the economy and the country. Consequently, one could easily consider shipping as a »heavy industry« of Greece. Anyway, figures and statistics can reflect only parts of the truth, as the industry is not only a major employer, but also a quality employer giving opportunities for personal development due to the inherent need of the industry for expertise and international profile of its people.

This is directly reflected in the number of shipping companies registered in Greece, estimated to 1,200 in 2010 and indirectly demonstrated in the Hellenic academia, where the state finances four fully dedicated university departments for the needs of the industry and ten marine academies. Public and private investments in education, training and related services, such as certification, make absolutely sense, as 16,000 Hellenes are mariners, almost 12,500 people are employed ashore and 200,000 jobs are related to the industry.

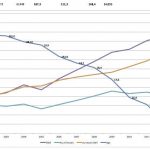

Apparently the credit crisis and low freight rates have influenced the contribution of the industry to the national accounts. Reduced revenues from the industry lead to lower contributions and this is also evident in the analyses of the Bank of Greece. As the Greek shipping industry is earning money from international trade, where Greece contributes with less than 0.5 %, the ominous macroeconomic condition of the national economy did not impact the industry. One could only highlight the issue of ship financing, where Greek banks could not support new projects. As per Figure 1, the fleet and the industry evolved substantially even during the crisis years.

The data provided by Petrofin Research portray clearly the dynamic of the industry in the last twelve years. Considering 2001 as basis year, the deadweight of the total fleet was 150mill. dwt and the average age was 21.4 years while in 2013 the fleet has reached 281 mill. dwt and an average age of 14.1 years. This implies a growth of 4.9% in terms of dwt and a reduction of the average age of almost 40% in the last years. Looking also at the number of ships, an increase of almost 1% p.a. or close to 10% in this period is reported.

Therefore it is clear that the Greeks have invested and acquired bigger and younger ships, even during the crisis. The statistics are even more positive when smaller vessels of less than 10,000 dwt are excluded: Then the average age of the fleet becomes 10.2 years. A similar result is derived when only ships over 20,000 dwt are considered: The average age drops to 9.8 years. Data from the same source indicate also that the concentration in the industry is increasing, suggesting that top 30 owners control almost 55% of the fleet (in terms of dwt) in 2013 vis-à-vis 50% in 2007. Concentration seems also to increase in top 50 and top 70 tiers of owners.

Statistics yield that the Greeks remain strong in bulkers and tankers. A number of 330 Greek companies operate almost 1,740 bulkers in 2013 of an average age of 10.3 years. In 2003, almost the same number of companies operated circa 1,400 bulkers of 19.5 years old. This substantial improvement in the quality of the fleet is also accompanied by an increase in the total dwt of the fleet (130mill. dwt in 2013 over 77mill. in 2003). Bulkers represent 46% of the total Greek fleet.

The same picture more or less is given by Petrofin for the tanker segment. In 2003, 677 tank vessels of totally 71mill. dwt and an average age of 18 years were operated by 90 companies. In 2013, the same number of companies operate 823 tankers of 111mill. dwt and of average age of 8.9 years. Tank vessels represent close to 40% of the total Greek fleet.

In the last years, fewer companies operate (24 in 2013 vs. 34 in 2003) more container ships. The total dwt of the Greek container fleet amounts to 14mill. tons in 2013 and the total number of ships to 254 with an average age of 12.2 years (17.5 years in 2003). It seems also that container ships of less than 10,000 dwt are rendered as obsolete.

The above statistics give a very positive overview of the Greek fleet and the industry. The average ship size is increasing while the average age is decreasing. This implies a younger fleet and quality tonnage that complies with all new regulations and fulfills the needs of charterers. Evolution and growth were sustained during the crisis, implying also that the respected market shares were increased. It seems that the appetite of Greek operators is not satisfied yet, however acquiring access to fresh loans and capital might be more difficult than in the recent past.

European ship financing sources seem either unwilling or incapable of providing loans for new projects. Some competition is expected from Far Eastern banks, however, spreads are expected the same and market conditions also more or less stable until 2016. Generally, a reduction of 6.3% in shipping loans is estimated in 2013. Greek banks have an exposure of 10.5 bill. $ in 2013 in contrast to 17.5 bill. $ in 2012. International banks with offices in Piraeus have also reduced their exposure by almost 10%, while international banks without local representation have slightly increased their exposure by 5.8% (ca. 20 bill. $ in total). The top 10 lending banks finance almost 63% of the projects, and almost 90% of them are still European – RBS being the leader with an exposure of 8.8 bill. $.

There is no secret recipe of the success of the Greek shipping industry. Greek owners are active in the same international playfield and face the same risks and challenges. Taxation is more or less the same, as the tonnage tax levels are comparable with all major European ones. They do not get any financing from the state and there is no hidden subvention to the industry, even for flagging-in or employing Greek nationals. So, which elements constitute the mix of success?

One might say that the comparative lower levels of leverage enabled Greek companies to survive the crisis. This is partially true, as it is retained earnings that magnified the growth in the last years of the crisis. While most of the competitors were dry of liquidity and the banks could not offer plenty of short-term capital, Greek companies enjoyed the benefits of being cash-rich. Some advocate that the listing of almost 20 companies in stock markets, such as of Stealth Gas, Diana, Paragon, Navios etc., offered increased visibility to Greece shipping. This might be true, yet one has to consider that »going public« is a difficult task and the total cost of finance might be higher than of conventional bank lending.

Definitely, the quality of the people in the industry, both employers and employees as well as of experts and consultants, is key towards success along with the deeply rooted marine and maritime tradition. As tramp shipping markets resemble to almost »perfect« competition conditions, shipping is predominately a game for rational and prudent players, and none can dramatically change the market. It seems that the mix of expertise, capital availability, cost-driven efficient management, prudency and rationality is determining success.

The most demanding challenge ahead – not only for Greek shipping, but also for the global web of shipping interests –, is international regulation. It is necessary for the industry to have a globally leveled playfield and therefore to have harmonized rules, especially in the fields of safety, security, human element and environmental protection. Unilateral initiatives might dilute the international character of the industry, and deem artificial fleet segments – or even worse – impose protectionism.

Recent environmental regulations, especially rules and provisos related to air emissions, raise concerns in the industry. The issue of CO2 emissions and compliance with sulfur regulations are heavily criticized, not because the industry is against environmental friendlier designs and operations, but because of the »uneven« playfield and the enforcement of gold-plated local or regional rules. Ships, as financial assets, cannot be replaced in short periods; ships, as technical assets, cannot be replaced as they serve almost 80 % of the volume of the international trade and there is no other viable and feasible technical alternative. Consequently, environmental regulation should be thoroughly consulted and its impact assessed before any formal consent.

Author: Prof. Orestis Schinas

Head of the Maritime Business School at

HSBA in Hamburg, www.hsba.de/en

Orestis Schinas