Operation areas, design trends and evolving new markets for this type of ship were discussed at the OPV 2011 Conference in Hamburg.

With the international recognition of the 12 NM territorial waters and the 200 NM Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) in »the[ds_preview] third United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea« (UNCLOS) in 1982 many navies and coast guard authorities were confronted with the challenge to control their country’s extended influence zone. At first glance this appears as a classical task within any navy’s field of duties. However, since many missions in the context of EEZ control have a quite civilian profile (e.g. search and rescue, anti-pollution and disaster reaction), the question was raised from the beginning whether it would be adequate and cost efficient to base offshore patrol on multi hundred million Dollar expensive frigates and corvettes only. Since those early years several countries approaches to a new class of ships, the Offshore Patrol Vessel (OPV), could be observed. OPVs have been considered as a promising market for both naval and civilian shipbuilders as well as the electronics-, sensors- and equipment industry, however, some high expectations had to be adjusted to reality over the decades.

On the OPV 2011 Conference, organized by Defense iQ in Hamburg on 20–22 September 2011, around 200 delegates from nearly 20 countries, including several Navy Chiefs of Staff and planning directors as well as senior industry representatives, discussed actual missions, fleet planning and trends.

»One design fits all?«

The Dutch international Damen shipyard group titled its presentation »Building the Ultimate OPV«, which provokes the question, whether one design approach could match all mission requirements, Watching the presentations of such different authorities as the US Coast Guard, the Royal Navy, the German Bundesamt für Wehrtechnik und Beschaffung (BWB), the Canadian, Finnish, Algerian and Trinidad + Tobago Coast Guards as well as the Navies of Turkey, Portugal, Italy, Poland, Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, Nigeria and Gabon, it soon became clear that the answer must be »no«. Due to the different geographical circumstances, but also because of the varying administrative and operative responsibilities in the countries there are very different OPV designs, ranging from a kind of research and service vessel in Canada and Finland (often called »white ships«) to the powerful US Coast Guard Cutters and to almost navy corvettes (»grey ships«) in Latin America. On the other hand, there are also many commonalities in the missions, which motivated ship designers and builders like Damen, ThyssenKrupp Marine Systems (TKMS), Lürssen, A&R, STX Canada, Austal and Fassmer to develop type designs with modular mission packages.

OPV missions and capabilities

Actual mission profiles for OPV may include a broad range of tasks: Especially for the police type missions, which also reflect the today dominating »asymmetric« threats, the importance of »off board« means such as helicopter or autonomous air vehicles (AAV) and fast interception boats is increasing. The most important weapon in anti-piracy and migration or drug interdiction missions has been the boarding party. With this trend the OPV can become more a »mother ship« rather than the acting device itself, which influences the required capabilities of the platform, for example the top speed.

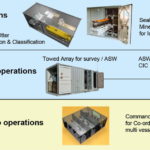

A widely discussed feature is the flexibility of the relatively small OPVs (typically 1,700–2,500 t displacement) to cover a maximum of roles by integrating exchangeable mission modules, e.g. in »plug and play« type containers. While the designs presented by most shipyards promote such exchangeable mission modules, users and naval system providers as Atlas Elektronik point out that there are some limitations for modularity (see Fig. 1).

Not all military roles (e.g. anti-submarine or mine warfare) are available for containerization in unlimited complexity, and specially trained crew would have to accompany the mission containers, which itself would have to be well stored and maintained in suitable port facilities when not installed on board. In naval practice some module pioneers as the Danish Navy (Stanflex Class) have given up the idea of exchanging modules within 24 hours and have used their ships with dedicated missions for longer periods instead.

Budget restrictions trigger new design trend

In particular potential OPV buyers in African and Latin American countries, but even wealthier national economies such as the United States, Canada and Germany are struggling with the fact that only rather low budgets are available for public duties such as controlling the EEZ, if any. During the OPV 2011 Conference a number of countries unveiled their OPV plans, coupled with the remark »no state budget yet in sight«. Thus »maximum impact for minimum life cycle cost« is the priority for any OPV project. To match this priority, a precise definition of the missions is mandatory. This leads then quickly to questions as:

• Which ship size is necessary for sustained operability in the area? (e.g. full operability in sea state 5, 25–30 days autonomy, 4,000–5,000 NM range in cruising speed)

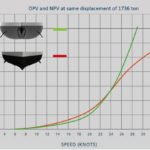

• Which top speed is really necessary? (25 kn instead of 20 kn needs three times more engine power which means larger, heavier and more expensive engines)

• How and to which extent commercial standards and »Commercial Off The Shelve« (COTS) equipment could be used?

• Which military standards are essential for the mission? (military standards are a major cost driver)

The observable trend is clearly pointing in the direction of being slower and more »commercial«. Civilian shipbuilders like the German Fassmer Group, having a long reference list for authority and Search and Rescue (SAR) vessels, have successfully entered the OPV market (see Fig. 2).

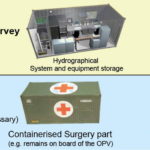

Modern multi-mission OPV designs, usually planned for a life cycle of 35 years and more, should have a certain growth potential for future new mission equipment and consider today’s space requirements for e.g. rescued boat people, jailed drug traffickers or pirates and injured persons in case of disasters. Sufficient facilities for off-board means as helicopters and interceptor boats are mandatory (see Fig. 3).

An interesting side note is that several designers promote now a stern launch and hoisting facility for interceptor boats, a system, which has proven high availability in heavy sea state on the SAR cruisers of the German Lifeboat Society (DGzRS) already for decades.

New focus areas: fuel efficiency and emission standards

According to published data OPVs spend most of their operational time in slow speed mode (< 15 kn) and 50 % even in the »loitering« range of 4–12 kn.

Since fuel costs become a more and more significant part of life cycle cost, a hull form optimized for slow and medium speed range as well as a modular propulsion concept for optimum use of the individual engines are key features (see Fig. 4). A typical OPV propulsion power of 2 x 4 MW (twin shaft) are proposed to be split into 2 x 2 x 2 MW. Electric motors of 2 x 0,5 MW could be added to each shaft, which are good enough for loitering speed, driven by the diesel generators which cover also accommodation and bow thruster’s load, or a full diesel-electric power plant could be considered. In the light of upcoming stricter IMO emission standards even LNG fuel has been discussed. It became obvious during the conference that there are different philosophies among the designers: some promote a simple and cheaper »classical« diesel plant while others offer more sophisticated, but situation adaptable modular and hybrid or electrical options, which would be a more expensive investment, but may help to keep fuel cost down during the life cycle. With a SWATH design the platform could even be smaller providing same seaworthiness, however, payload consideration must be done carefully.

Michael vom Baur