Taking most prominent examples into account, presents impacts of wasteful thoughtlessness in yacht design. In many cases time spent at port is hardly considered …

Dreams and reality differ – in real life as in yacht business. There are countless disputes between owners and yards whether[ds_preview] the delivered vessel fulfils the specifications. If specifications have been overlooked or misinterpreted, possibly because they left room for interpretation, a posteriori attempts to meet owner expectations are always expensive, and sometimes impossible.

But even more often the specifications simply do not reflect the owners’ real interests. Sometimes the owner does not know what is possible or available. Sometimes, features are specified that the owner does not need, but pays dearly for. In either case, the owner’s interests are not best served. Below we illustrate in some examples how standard wording in specification, frequently introduced by »copy & paste« from previous building contracts, can result in expensive over-engineering or falling short of significant gains in owner satisfaction.

»Unlimited world-wide operation« or »restricted operation«

Typically the contract specifications of a yacht contain a statement that the yacht shall have »unlimited world-wide operation«. This sounds like a fine statement to copy from one building specification to the next. However, on closer inspection it is highly questionable for customised yachts. No other marine vessel is designed to meet so many extremes. Instead, reasonable compromises for each vessel type are found.

Yachts are typically built following (directly or indirectly) the regulations for cargo vessels. In addition, they are designed for highest comfort demands. In the end, yachts simply cannot fulfill these extremes, but much time and money is spent to get close to these extremes, which is wasteful and nonsensical.

What does »unlimited world-wide operation« mean for the structural design? The regulations for cargo vessels then assume operation in the North Atlantic with 16.5 m significant wave height (as a rule of thumb this means 33 m maximum wave height) over 320 days per year, over the whole lifetime of the vessel. This may be a conservative, but arguably justifiable assumption for cargo vessels which have little alternative in trading patterns. But how realistic is this for yachts?

In first approximation, for half the significant wave height you will have half the wave-induced loads. As opposed to »unlimited world-wide operation«, this would still mean significant wave heights of 8.25 m or 16.5 m maximum height. And yacht operation in such sea states is highly unlikely.

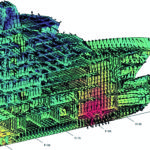

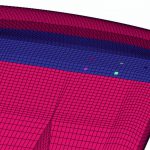

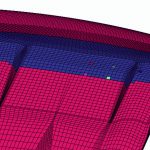

Direct simulations for alternative dimensioning of structures are recognised by almost all classification societies. Such simulations can predict the loads for a given significant wave height, as required for the tailored structural design and approval. The list of what could be done with all the structural weight saved is virtually endless. And in view of the current prices for steel (or even fancier building materials), the saved material alone pays for the costs of such simulations.

»Safe Return to Port« (SRtP) regulation is another argument to think carefully about specified operations. In some cases, large yachts may be operated with so many passengers that SOLAS passenger vessel regulations including »Safe Return to Port« are applicable. For restricted operation, requirements for essential systems, particularly for so-called safe areas, according to SRtP and life-saving appliances are far less strict. This reduces costs. But often much more importantly, it gives more design freedom resulting in more comfort and pleasure for the owner on board e.g. life rafts, easy to be hidden, instead of lifeboats.

»Unlimited world-wide operation« is a technical term used by classification societies. It implies the strictest assumptions for encountered waves and associated loads. It does not mean that the vessel is permitted operation everywhere in the world. Many sea areas have additional requirements imposed by national authorities. These concern mostly environmental issues, e.g. emissions to air or underwater noise. The Glacier Bay special regulations, for example, contain specifications for air emissions, water emissions and underwater noise. Similar special regulations are under development for some European waters. Such local restrictions should be considered in design and thus be addressed already in the specifications.

Noise and vibration – design for high sea or port?

International noise level resolutions for marine vessels like IMO A.468 (XII) »Code on Noise Levels on Board Ships« were developed to ensure minimum work and living standards for crews on merchant ships. Consequently, they fall short of comfort requirements for luxury yachts by a large margin. It is therefore common practice to include individually determined noise specifications in building contracts for luxury yachts. These specifications vary and are usually functions of the type of rooms and the operational conditions.

In our experience, most such building specifications for luxury yachts impose too harsh limits for operation at sea and focus not enough on conditions at anchor. However, in reality, most luxury yacht owners spend most of their time on the yacht when she is at anchor or in harbour. As a consequence, much effort is misdirected to make the yacht »quiet« for open-sea operation. This effort could be saved, or better invested into making the yacht quiet at anchor, e.g. by installing better HVAC systems or other low-noise devices. Of course, work spaces would still comply with IMO regulations for noise and vibration level, but the focus of the effort would be directed towards the public spaces for the owner and his guests.

A similar mismatch is observed for vibrations. All contracts include specifications for vibration levels from main engines, shafts and propellers, focusing the design attention on vibrations for the vessel at speed. Here the condition at anchor is often thought to be uncritical. However, ship motions due to swell or wind sea may induce stern slamming and highly uncomfortable vibrations in this case. This happens, for example, if the yacht anchors with the stern to the open sea in otherwise sheltered conditions. It is recommended to include this issue in the contract specifications to ensure that it is addressed during the design phase.

Normally not stipulated specifications for stability

Of course, each vessel has to fulfil the stability requirements of SOLAS. However, large yachts may be upgraded later in their life by adding e.g. a pool or helicopter landing pad. As large yachts often are already near stability limits, it is recommended to specify a larger stability margin to keep the option for later upgrades. Modern hull design approaches employing formal optimisation investigating thousands of design alternatives enable larger stability without compromising design speed. Formal hull optimisation can also be used to reduce the carbon footprint significantly. Efficiency gains of up to 10 % have been reported.

Another critical specifications item concerns the auxiliary systems. These are most often used in harbour or at anchor, but designed for extreme operating conditions (e.g. hot air and water temperatures, 110 % load). The systems should be designed with a high degree of flexibility to cope with this large gap between design load and typical operational load. Classical examples are the cooling water systems and the engine room ventilation system.

Modern energy flow simulations can analyze the dynamic system behavior for various operational conditions and rapidly compare design alternatives. Such analyses allow appropriate tailoring of systems avoiding excessive overdimensioning. Appropriate systems are not only more efficient leading to smaller carbon footprints. They also are generally more compact and give the designer more leeway to improve other aspects of the vessel. Design of major auxiliaries should therefore follow »dynamic energy system simulations« and this should be specified in the building specifications.

Conclusions

The above examples illustrate how appropriate specifications can save unnecessary costs, weight and space in yachts. The savings can be used in part or total to design and build a better yacht for the owner. In summary, owners (or their representatives), designers and yards should reconsider if common »copy & paste« building specifications really reflect the owner’s needs.

Author:

Axel Köhlmoos,

FutureShip GmbH, Hamburg

axel.koehlmoos@GL-group.com

Axel Köhlmoos