Nowhere in the world exists such a huge demand by the offshore oil industry than in Brazil. That’s why foreign maritime suppliers are rushing to take advantage of this market.

Among the clouds of stagnant economic growth and slackening industrial output, Brazil’s offshore and naval activities shine like a cluster[ds_preview] of brilliant stars. In its recently published Strategic Business Plan for the 2014–2018 time period, the Petrobras group forecasts investments of 221 bill. $ in well over 900 different projects. Two thirds of that impressive sum are destined to explore and exploit the country’s oil and gas reserves.

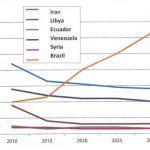

As of today, the reserves amount to 16.6 bill. barrels of crude and 451 bill. m3 of gas – still far behind the deposits of various major OPEC countries, but far less endangered by violent unrest and armed conflict than the oil stocks in other parts of the world. Moreover, output is growing at a faster clip than in many rivaling oil states (Fig. 1).

At this year’s World Economic Forum in Davos, Petrobras chairwoman Graça Foster predicted that Brazilian oil production will swell from its present 2mill. barrels/day to 6mill. by 2035, lifting the country to the sixth position in a global ranking of crude oil producers. The US Energy Information Administration agrees with this forecast, and the Vienna-based International Energy Agency expects Brazil to become a net exporter of crude again as early as next year. (The status had already been acquired, but was temporarily lost.)

Other experts point out the fact that, so far, only one sixth of the country’s promising offshore areas have been seismically mapped, which opens a perspective of future additional discoveries. Petrobras itself says that 50% of all new findings of oil and gas since 2005 world-wide have been made in the pre-salt layer and almost two thirds of these deposits are located under Brazilian territorial waters. The company’s drilling engineers boast of an almost unheard of success rate in the oil industry’s history: 82% of all well-heads brought down by them turned out to be profitable. Since mid-2013, Petrobras made no less than 46 new discoveries, 22 of them onshore, 24 offshore and 14 of the latter in ultra-deep oilfields of up to 6,000m below the sea level.

The pre-salt saga began only eight years ago, when Petrobras tapped the Tupi field in the Bay of Santos and made headlines at home and abroad by sending out photos of former president Lula, who dipped his hands in the newly discovered black gold. Meanwhile, oil output from the company’s pre-salt fields alone has shot to half a million barrels per day – a quarter of Petrobras’ total current crude production and the same volume which the group pumped up from all of its well-heads by the mid-1980s.

In the wake of the recent oil boom, Brazil’s naval industry has also risen from several decades of hibernation. In 2003, Petrobras’ transport division Transpetro drew up an initial order list of 38 production platforms, 28 drilling rigs, 88 oil tankers and 146 supply and support vessels. »When it did so, our country had not even the shipyards where this equipment would be built,« recalls Paulo Alonso, an assistant to Petrobras chairwoman Foster. »So most people dismissed the whole idea as utopian.«

It is easy to understand why launching such a huge program could hardly be achieved other than by fits and starts. Of the 49 vessels which Transpetro hopes to make operational by 2020, only seven were delivered so far – due to delays in shipyard construction, lack of qualified manpower and technical know-how as well as shoddy manufacturing procedures. Several times Transpetro chairman Sergio Machado had to fine tardy suppliers or to warn them that contracts would be cancelled, if deliveries were not made on time. »But the situation is rapidly improving«, the executive said earlier this year and bolstered his assessment by ordering another lot of eight vessels.

Probably the best example of how the Brazilian ship-building industry has pulled itself together in order to meet the tremendous new challenges is the Sete Brasil holding. Several pension funds, three investment banks, the US private equity group EIG, some individual investors plus Petrobras as a minority shareholder are allocating 6.4 bill. $ in proper resources and looking for 19.2 bill. $ in public and private loans to order a total of 29 pre-salt drilling rigs from five Brazilian shipyards. The first lot of nine rigs will be built in 2015/16, the second lot of 12 rigs in 2017/18 and the third and final lot of eight is scheduled for 2019/20. Seven of the first nine rigs belong to the traditional class of drilling vessels, the remaining two will be designed as semi-submersible platforms. Sete Brasil explains that it will purchase an average of 40% of necessary equipment abroad, primarily in Norway, the US and the UK. However, says chairman João Ferraz, other foreign suppliers including German companies offering specific and technologically innovative components and services are also »welcome to make a bidding«.

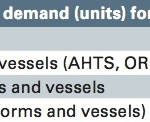

Current estimates for Brazil run to about four dozen major and minor shipyards working on 375 different projects, while the Transpetro order list for the 2013–2020 time period mentions no less than 350 units of all kinds to be tendered shortly (Fig. 2). Some companies who recognized this potential early on are already expanding their activities in the Brazilian market. Flammenfilter from Braunschweig/Germany, which operates in Latin America under the Protego brand name, began to serve local clients by selling finished safety equipment to them. This year, Protego opens its first assembly line in Brazil, and CEO Sascha Pineda does not exclude the option to produce high pressure valves in that country from scratch. »If you are aiming for long-term growth, local production of your equipment is inevitable«, says the executive. For one thing, it helps the company to forearm against a fluctuating currency, and for another it keeps it competitive in a market, where rivaling suppliers tend to overcome their former technological handicaps. Leser from Hamburg, another supplier of safety valves, and Ruhrpumpen from Witten/Germany, follow similar strategies. Leser will start producing in a plant near Rio de Janeiro in autumn of this year and expects to hoist the local content of its output to more than 60%. Ruhrpumpen already operates a plant in the Duque de Caxias suburb of Rio and offers, among other equipment, rotary pumps which inject sea water into offshore deposits to make the crude oil flow free.

»It’s safe to say that at this moment nowhere in the world exists such an enormous demand by the offshore industry than in Brazil, and hence you’ll hardly find more interesting opportunities for foreign maritime suppliers than here«, affirms Jürgen Friedrich, head of the Sao Paulo-based consulting group German Trade & Investment (Fig. 3). Even enthusiasts like him, however, agree that the size of the market alone does not yet guarantee commercial success – nor does an initial lead in technological know-how.

That’s why Martin Kunze, Managing Director of MAN Diesel & Turbo (MDT) from Oberhausen/Germany, which sells naval engines and compressors in Brazil and other parts of South America, advises newcomers to risk their chance only with the help of trustworthy local partners. »These people know every little legal, commercial or administrative trick which a beginner in all likelihood still ignores,« he says. Joachim Fritz, CEO of Leser do Brasil, concurs: »If, for example, you visit a client installation and your local sales representative or service engineer is on a first name basis with everyone you meet in the hall, that’s a good signpost on your way to a deal.« Concludes Pineda of the Protego group says: »Never forget that Brazilians like to buy from other Brazilians. So why not grant them that favor, if you want to do business with them?«

Kunze of MDT reminds fellow executives about other important aspects of the Brazilian offshore market. »One doesn’t haggle with a client like Petrobras, who purchases to the tune of billions of dollars,« he insists. Newcomers should also grow used to the fact that to register as a supplier, to have one’s products or/and services certified and to compile the necessary documentation

is a process which consumes much more time and energy in Brazil than elsewhere. On the other hand, procurement methods are realistic and transparent, says Kunze, and above all: »Petrobras is not a client who’ll walk away with a supplier’s valuable know-how.«

The executives quoted above and other experts like Adilson de Oliveira, an economist at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), tell foreign suppliers not to be discouraged either by Brazil’s local content clauses for the offshore and naval industries. On paper these clauses look indeed severe: up to 85% of local content for onshore fields, 57 to 67% for fields in relatively shallow waters, and 35 to 57% for deep sea reserves. »But it’s obvious that a giant project like building the infrastructure for the use of our pre-salt reserves cannot be mastered by Brazilian companies alone«, says Oliveira. Moreover, Petrobras’ management knows that in many cases their company will fare better if it pays a fine and buys foreign than if it accepts overpriced domestic equipment. Many foreign suppliers have also discovered how to make local content clauses more palatable by stretching their application over time.

Conversely, Petrobras chairwoman Foster caused quite a stir recently, when she explained that, given previous delays, a speedy ramp-up of crude oil production must now have precedence over local content exigencies. Otherwise, Brazil’s economy could miss the »window of opportunity« which opened, when Tupi and the other large offshore oil stocks became accessible.

Lorenz Winter