Economies of scale are what bulk shipping is all about. looks at how the current bulk fleet has evolved in recent years and what the future holds for the individual segments

Throughout the last 30 years, shipping investors have constantly sought to outperform existing vessels designs in terms of capacity within[ds_preview] the same dimensions or simply by building bigger ships. As a result, the interpretation of ship categories has changed over time and ship-owners as well as cargo-owners and port operators alike are wondering where vessel- and parcel sizes are headed.

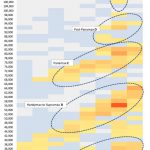

Handysize

The handysize-segment used to be relatively well separated from the handymax-segment in the last millennium, although most of the blue fields between the two segments actually contain small numbers of vessels. A structural shift can be noted late in the ‘90ies, when the deliveries are starting to focus on the upper margin (~28,000 dwt). However the most pronounced change is taking place during the 2005–2014H1-period, where the vessels push through the 30,000 dwt-threshold and edge up to just below 40,000 dwt.

It is interesting that the orderbook (based on CRSL also) from 2014H2 onwards contains almost no bulkers of the previous handysize-capacities above 20,000 dwt but instead shows contracts for 315 bulk carriers with capacities between 34,000 and 39,999 dwt. Also, it is worth pointing out that the largest of those vessels are reaching dimensions of the previous »Handymax«-area. The bulk of deliveries in 2010–2014H1 stayed within the dimensions of 180m length, ~28.4 to 30.0m beam and has draughts of ~9.5 to 10.9m. When the capacity of the vessels starts to exceed 39,999 dwt, both length and beam seem to surpass those margins.

From Handymax to Supramax

The term »handymax« commonly used to refer to vessels of up to ~45,000 dwt, but as the figure suggests, the vessels have been growing rather continuously, gradually passing the 60,000 dwt-threshold during the last four years and are set to grow even further according to the orderbook. This is starting to be a bit of a problem for market analysts, because the 60,000–80,000 dwt range was normally considered to be the »panama« segment.

In the 2010–2014H1-period, most vessels were delivered in the 56,000–59,999 dwt-range (842 units). Except for some deviations, the industry standard of those vessels seemed to be: ~190m length, ~32.3m beam and 12.8m draught. Regardless of the recent »popularity« of these units, the orderbook is visibly skewed towards the segment 60,000–65,999 dwt. These vessels have about the same beam, but are up to 199.9m long and have draughts of ~13.0–13.3m, so the handymax-segment will evolve further. A term often used to refer to these new, bigger handymax-bulkers is »supramax«.

Panamax

The largest amount of the old panamax bulkers – at least those vessels that can still be found in today’s merchant fleet – never exceeded capacities of 75,000 dwt and a beam of 32,2m in the first place. But over time, the vessels became longer and their capacity grew, finally even surpassing the 80,000 dwt threshold. In the 2010-2014H1-period, no less than 479 vessels whose capacity lay between 80,000 and 83,999 dwt and whose beam did not exceed 32,3m have been delivered. The average draught of these ships was ~14.4m and their length varied between ~225 and ~235m. Panamax bulkers which have been built 20 years ago normally did not exceed 225m and had an average draught of ~13.4m.

The industry has coined the expression »Kamsarmax« to refer to relatively large panamax-bulkers (~82,000 dwt), which can still call in the bauxite terminal in the Port of Kamsar (Guinea), because of their length not exceeding 229m.

Post-Panamax

During the last 10 years, a concentration of deliveries as well as contracts between 86,000 and 97,999 dwt can be observed. Since 2010, 200 vessels with capacities between 92,000 and 95,999 dwt have been delivered, seemingly marking the centre of investor interest in this segment.

The thing that particularly the vessels in the narrow segment of 92,000–93,999 dwt seem to have in common is their beam of ~38m as well as the length of ~229m–230m and a draught of mostly ~14.9m The slightly bigger units around ~95,000 dwt typically are about ~5m longer but have a slightly smaller draught (~14.5m) according to the data from CRSL.

Something new?

In the size segment of ~115.000 dwt, something astonishing has happened: This area of the matrix was virtually empty during the past years before recently deliveries spiked. But since the current orderbook is negligible, no clear trend can be identified. The largest group here are 61 vessels with an average capacity of ~115,000 dwt and a beam of ~43m. Their length varies between ~250 and ~254m and their quoted draught varies narrowly around ~14.5m with only a few noticeable exceptions (~12.2m). It seems that these vessels are filling a gap that existed due to the (as of today still valid) restrictions of the »old« Panama Canal. Some of the units in this segment are being referred to as »baby-capers« in the press. The units from the adjacent areas in this segment are shorter/longer or have a smaller/bigger draught, but all of them have a beam of ~43m.

Capesize

In the larger segments of the bulk carrier fleet, an ongoing expansion of the vessel sizes can be observed as well. Although the fleet still contains some old capers of around 120,000+ dwt and especially between 140,000 and 159,999 dwt, theses types have lost market shares fast since ~2000. In the new millennium, the ordering activity clearly shifted towards the 170,000+ dwt segments and in summer 2014, Clarksons orderbook featured 174 further bulkers with capacities between 180,000 dwt and 189,999 dwt but only 17 ships with capacities between 150,000 dwt and 179,999 dwt.

As far as the dimensions are concerned, the vessels with 170,000–179,999 dwt generally (with a few rare exceptions) have a beam of ~45m, a length of ~292m and a draught of ~18.2m.

As far as the 180,000+dwt vessels are concerned, the picture is less clear, with some vessel’s beam exceeding 45m and some vessel’s length reaching up to 295m. Four vessels of the 180,000–189,999 dwt-segment probably rather belong to a segment on their own, judging by their dimensions: In the summer of the last year 2014, 175 bulkers had capacities of between 200,000 dwt and 209,999 dwt.

The largest part of those ships did not exceed ~300m in length or ~50m in beam and generally seemed to stick to a draught of ~18.2m (again, with a handful of exceptions). Another 95 of these vessels (200,000–209,999 dwt) can be found in the orderbook, together with the aforementioned 174 vessels with a capacity between 180,000 and 189,999 dwt.

VLOC

In the segment of Very Large Ore Carrier (VLOC) with around 250,000 dwt capacity, zero vessels have been completed in the first ten years of the new millennium. Hence the 22 vessels which came into service since the year 2010 as well as the orderbook featuring 39 vessels are a bit of a revival. Their standard dimensions seem to be around 330m length, 57m beam as well as around 18.1m draught – all of which with minor deviations.

Above 260,000 dwt, VLOCs have been delivered in surging numbers in recent years, but the colour-pattern suggests that they did not really evolve in size but rather simply (re-)appeared along the booming Chinese iron ore import demand.

Suggestion for further analysis

The graphic analysis of the bulk carrier fleet suggests that the evolution of bulk carrier-sizes is a reality for all segments from handysize to capesize. Whilst in academic theory the desire to increase the parcel size in order to benefit from the economies of scale is being felt most intensely in the smaller segments, even capsize ship-owners seem to have been wooed by the economies of scale in recent years. Next to the desire to outperform the current standard market dimensions, the (anticipated) widening of the Panama Canal (locks) as well as the exploding Chinese iron ore demand since ~2003 seem to have generated a lot of investment in »new« vessel dimensions. It will be interesting to see, how these will evolve in the future.

Also, it would be interesting to see, if there also exists a cascade-effect in the bulk trades in the form that vessels, which once had been deployed on typical trade routes for typical commodities, are being replaced by larger units and are in turn replacing smaller units in their respective trades. This could for example be researched by looking at older broker reports and creating databases featuring the vessels size, cargo size and cargo type as well as origin and destination and year of the voyages contracted on the spot-market.

This kind of information may not always be present and it stands to be biased to a certain extend by the vessels which have been employed in industrial-shipping activities and hence left no paper trail in brokers journals or the trade press, but it would be an interesting research approach nonetheless.

Michael Tasto