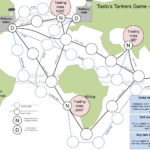

Serious gaming is widely en vogue. Michael Tasto proposes the »Tanker Market Game« for students to improve the understanding of the mechanisms at the spot market and the shipping cycles

The idea is simple. Students are divided into cargo owners and shipowners. As in most games, whoever owns most cash[ds_preview] at the end of the game wins. The charming differences here are:

The shipowners are competing against each other and the cargo owners are too, so each group will have one winner.

In order to win, both groups need to interact in different combinations as they encounter each other in the trading areas randomly during the game.

Since all cargo owners receive the same amount of oil, the difference in their earnings must come from skilfully negotiating low freight rates. Since all shipowners start with the same amounts of ships and cash, the difference in their earnings must come from clever routing of the vessels as well as skilfully negotiating high freight rates.

Necessary compromise

Life is compromise – and so the level of detail had to be reduced. Initially, the world-map was featuring a fourth trading area and more interim fields. Also, it was planned to incorporate two sizes of tankers and cargoes as well as realistic costs for moving or idling the vessels. Those ideas had to be abandoned in order to keep the game playable:

A second set of vessels would have required different cost sheets and the goal of the game was to understand the dynamics of the spot market, not the various costs of vessels or the spill-over effects between size segments. Also, realistic costs would have required exchanging play money in awkward amounts. So exemplary figures, which introduce the idea that going faster is more expensive, have been used instead.

More interim fields, refineries and trading areas would have reflected the geography of the crude oil trade more accurately. But it also would have meant that students would encounter each other less often on the spot market.

Before the game

Before the game, the students are organized into groups: After the rules are explained and the first round of cargoes is deployed to the trading areas the shipowners can decide where they want to place their vessels on the map.

The Tanker Market Game starts

The game is played in rounds. Each round consists of three stages:

oil delivery

negotiations

payments and movements

Stage 1: Oil delivery1

Every third round, the cargo owners receive two cargoes each, drawn from a hat. The cargoes are placed in storage areas of the cargo owners (not pictured here). The cargoes must be shipped according to a first-in-first-out scheme, which prevents the cargo owners from clearing the short-haul cargoes from storage first. In all other rounds, this first stage is skipped.

Stage 2: Negotiations

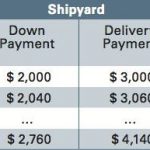

During negotiations, shipowners can talk to cargo owners but only if they meet in a trading area (»N«). If both agree on a freight rate, a cargo form is filled out and the cargo is loaded to the ship. During negations, shipowners can order new ships or sell ships to the scrap yard at prices announced by the game leader2 or to each other.

If ships in trading areas do not reach an agreement during negotiations, they incur idle costs. If cargoes remain in trading areas after negotiations, storage fees incur. The time limit for the negotiation phase is 120 seconds. Negotiations can only start when all cargoes are on the map and the market is thus »fully informed«.

The cargo owners (and shipowners) only get paid in stage 3 (and the voyage can only begin) if a complete cargo form is handed to the game leader during the negotiation stage. If a freight rate has been agreed upon by cargo owner and shipowner, but the cargo form has not been completed, both the vessel and the cargo remain idle. If several cargoes meet with several available vessels the negotiations can become quite vivid. All ships are potential contract partners to all cargoes but only if they meet in the trading area. It is possible that cargo owners fix contracts with different companies at the same time and vice versa – provided they fill out the form and meet in the trading areas.

If no negotiations are possible, the stage is skipped. Also, the stage can be ended prematurely if all participants agree.3

Stage 3: Payments and movements

The cargo owners receive money for cargoes that are successfully loaded (completed cargo form) from the bank and pay penalties for cargoes that remain unshipped to the bank. The cargo owners pay the contracted freight rate to the shipowners and load the cargoes to the vessels.

The shipowners choose the fast or slow route for the newly signed contracts and pay the cost to the bank according to the cost sheet. Each vessel that is already on a route moves one field further. The routing is binding and vessels cannot simply turn or switch lanes. Vessels in a trading area without cargo can either sit idle or travel to another trading area. Both the costs for sitting idle or moving to another trading area are paid to the bank. When a vessel arrives at a refinery, it is emptied and the shipowner must choose a route to another trading area in the next round.

Newbuilding and scrapping

Shipowners must pay the yard if they have ordered vessels in the negotiation stage or receive money for scrapped vessels (also declared in negotiation). When all vessels have been moved/all parties have paid idle/storage/voyage costs the round is completed and the next round can start with the first stage.

Shipowners’ rules

The shipowners …

earn money for transporting the cargo – depending on the negotiated rate

have to pay depending on the chosen route

have to pay idle fees for vessels which are not being moved

Generally, shipowners decide to which trading area they are sending their ship. In trading areas, they can pick up a cargo, if they agree on a freight rate or succeed in negotiations against other shipowners. Shipowners are not allowed to build cartels or fix prices.

Winning and losing for shipowners

The game ends if a shipping company should go broke and has no more vessels to sell. At the end of the game the shipowner with the most money wins. Thereby all ships will be valued at the current newbuilding price.

Cargo owners’ rules

Like the shipowners, the cargo owners are not allowed to enter cartels or fix prices. The cargo owners …

earn 5,000$ for each cargo that is loaded to a ship and documented in a cargo-form

have to pay freight rate for shipping the cargo as agreed with the shipowners

have to pay 100 $ at the end of each round for every cargo parcel which remains in the trading areas

The latter is supposed to prevent sitting out, although it should become clear to the cargo owners fast that sitting out means not earning money on the cargoes whilst competitors start piling up cash.

Filling out the cargo form serves two purposes. First, both parties can look up the details of the contract again, and second, it allows a decent analysis of the freight rates later on.

Winning and losing for cargo owners

At the end of the game, the oil company with the most cash wins. Unshipped cargoes are not counted. Oil companies cannot go broke, they simply stop paying storage fees.

Tasks of the game leader

The tasks of the game leader are:

overseeing that the rules are being followed

announcing start and end of the negotiation stage as well as the different stages and rounds

dispensing cargoes

management of the bank

management of the shipyard

asking individual questions during the game: »What are you observing?«, »Why did you just pay so much?«, »Why have you not been able to agree on a higher or lower freight rate compared to last round?«, »Do you currently think it is better to be a shipowner or a cargo owner?« …

keeping track of the interim scores every 20+/- rounds

Some finer mechanics of the game

The game begins with a severe capacity shortage. At first, this is hidden because in the first round, the trading areas are cleared fast and the effective shortage of vessels is not being felt. After a handful of rounds, the cargoes start to pile up in the storage areas and the students realize that cargoes are coming in faster than the ships can transport them. As a result, the cargo owners will start to panic, because in order to win, they need to ship their cargoes. Also, faced with increasing storage costs, sitting out is not an option, so the bidding process is likely to begin early, provided the students have a keen economic instinct. If not, some random hints about the comparability to an auction process can be thrown in.

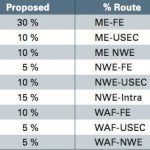

As three oil companies are receiving two cargoes each every third round, the demand can be expressed as 2/round. As a function of the cargo-mix and the average haul, the effective transport supply of the initial ten vessels can be calculated as ~1.3/round, using the slow lanes or ~1.8/round, using the fast lanes. The market is thus experiencing a capacity shortage from the beginning on.

The aim must be to yield a demand slightly bigger than the supply of the fast lanes, so that the cargoes will pile up and the cargo owners will enter into a bidding war for the scarce vessel capacity, driving up the cash surplus on the side of the shipowners, who will likely identify the opportunity to buy more vessels to earn more money.

End of the game

The game either ends …

after the shipowners decide to scrap vessels in large amounts,

if a shipping company goes broke and cannot sell vessels to the scrap yard or

if the game leader sees fit

Test run and verification

The first test run of this game was conducted during an ISL training of a class of M.Sc. students from Saudi-Arabia, whose subject of study was logistics but who did not have prior experiences with the theory of the spot market or shipping cycles. The trial run was a success. After ten rounds the game was understood and after 20 rounds the students were »hooked« and paying full attention to everything that was happening on the board and around it, discussing strategies or simply enjoying the sometimes hilarious outcomes of the spot markets, where cargoes would be fixed for rates three times as high as the round before. At this point, all the moderation that was required, was to announce the rounds and the start/end of the negotiation stage as the students had already taken over exchanging the play-money.

Results

In the first run, the rates soared faster than anticipated. When the other shipowners realized that the »green shipping company« had placed an order for a new vessel, the orderbook exploded, with some companies ordering two vessels right away. Within a short time, the fleet capacity was set to double.

At this point, the market was doomed for oversupply because the demand stayed constant at 2/round whilst the supply of transport was set to increase to at least 2.6/round (on the slow lanes). This development would not become visible before the delivery of the vessels (by design: 30 rounds after ordering) though and when the first wave of vessels hit the waters, they were cheerfully welcomed. By then, the answer to the question »Is it better to be a shipowner or a cargo owner« had unanimously been answered with »shipowner«. But this market had it coming and after a few further rounds, the sentiment in the room was changing. The storage areas were cleared and instead of cargoes, the vessels kept piling up and idling in the trading areas. The once hectic cargo owners were leaning back relaxed and played the shipowners against each other. The game continued for some rounds with more vessels remaining idle on a regular basis and the active fleet »slow-steaming«.

Verification and hidden elements

Playing this game, the students are experiencing the conundrum that shipowners seem to maximise their profits when their voyage costs are highest. Also they experience that even in a market that is fundamentally oversupplied with ships, occasionally a favourable imbalance of cargoes and vessels may occur, sending the freight rates on a roller coaster ride.

Also, the students have been faced with the dilemma of having to organize (and pay) for the ballast voyages as well as the sometimes costly need to sit out and wait for better times or the costly relocation of the vessel to a more prospective trading area. Some of these elements can be touched upon in later lectures, when the negative risk premium of the time-charter rates is explained. Additionally, the criteria of perfect competition can be discussed, based on the game experience.

In this case, the students were asked how they perceived the negotiation position of the shipowners at the beginning of the game (»very strong«), as well as at the end of the game (»weak«). When asked what went wrong for the shipowners the students concluded: »We have bought too many ships.« What else is there to say?

Author: Michael Tasto

Institute of Shipping Economics and

Logistics (ISL), Bremen, tasto@isl.org

Michael Tasto