Only a minority of super yacht owners put the protection of the environment at the top of their list of requirements. But builders are investigating ways of producing yachts with lower carbon footprints, whether building new or refitting.

Polling a number of yacht builders on whether they believe it is better to refit a super yacht or build[ds_preview] new, purely from an environmental point of view without taking into account financial considerations, compelling evidence is forthcoming that building new wins – at least in the long term. Only motor vessels were considered, since sailing yachts clearly eat up miles with minimal fossil fuel consumption. Three parts of the »life cycle« are taken into account in the Eco-indicator 99 impact assessment method: production, use and disposal (scrapping / recycling). A major refit is defined as »taking at least six months« by both Cristian Schwarzwalder of Blohm + Voss Yachts and Ronno Schouten of Feadship – possibly involving lengthening the yacht or including a complete new interior with new equipment.

Disposal: recycling or scrapping

Disposal through recycling or scrapping a yacht is usually ignored since there is always somebody who will pick up an old hulk and keep her afloat – Vitters’ Louis Hamming says »I have never seen a yacht scrapped. Even if they are years old and should have been left in the mud, there is always somebody with a nostalgic idea that takes them out of the mud and starts with a project much worse than a new build! People always see (emotional) value in something old and scruffy.«

Vincenzo Poeri of Benetti, nevertheless, believes that investment needs to be made to find ways to recycle, and that while existing yachts should be refitted – respecting the new environmental technology and rules – once it is no longer economically convenient, they should be recycled: »boats over 30 years old will then be scrapped rather than refitted«.

As a last resort, recycling the steel / aluminium of a stripped-out super yacht does give some benefit, avoiding the production of new materials. Feadship has never scrapped a yacht, nor has an expected lifetime for them, but states that »due to recycling, scrapping is actually beneficial for the environment – copper and more expensive materials like the propeller and gold in the interior could be recycled«, adding »Most of the woodwork and insulation will be hard to recycle«. They reckon on an environmental impact »credit« of 240,000 eco-points (explained later), assuming three quarters of the steel and aluminium can be recycled.

Kingship, builders of »Green Voyager«, believe that at least 80 % of the weight of a yacht can be recycled, including wooden furniture, also pointing out that CAT engines have a rebuilding program. Diana Liang (Sales & Marketing Director) adds »there is no question that selling the yacht on to be used will return more than scrapping«. She states »Scrapping is highly polluting, but since it almost never happens for yachts, it must be considered a low environmental risk« – »IMO conventions yet to come into force on hazardous material and scrapping will vastly minimize the effect this has on the environment«.

The two builder opinions appear to be contradictory. In fact, even if there is pollution when scrapping certain parts of a yacht, as long as a good amount of metal is recycled – thus preventing extra production of these materials (which is unfriendly to the environment) – then the net result of disposal can be positive for the environment.

Production: building or refitting

Between production and use, the environmental impact clearly depends upon how much the boat is used. Feadship’s research data indicates that the impact of »building a yacht is in general ›only‹ equal to one or two years of cruising. Therefore building a new more environmentally friendly and more efficient yacht may indeed be better for the environment«.

Kingship does not make assumptions about how often a super yacht is in use, as it varys quite a lot, some rarely leaving port. Nevertheless, they have environmental procedures at the yard to minimize production impact on the environment. A category which is difficult to measure, except for the emission of volatile organic compounds / VOCs. They believe building a new yacht has less damaging impact on the environment as »a major refit involves double the work and energy – removing old, then installing new items, this process risks causing a lot of pollution and waste«. »Green Voyager«, billed as »the world’s first unique custom Hybrid Superyacht« and the first 24 to 50-metre yacht to be awarded the RINA Green Plus Platinum certification, uses Siemens’ SISHIP EcoProp system, allowing powering by diesel, diesel electric and battery, or batteries alone. The philosophy behind this is to »use every litre of diesel burned or store it for later use«.

Nicholas Stark of Hanseatic Marine, the builders of »Silver«, which was built according to SOLAS, believes that »Diesel electric is a double-edged sword: fundamentally the same energy is still needed to propel the hull; you still need to burn the diesel. The lightweight, efficient hulls we have built to date are the result of a conscious decision to minimize the environmental footprint of our boats. The use of highly optimized hulls and lightweight structures will combine to have significantly less impact on the planet’s oil reserves than a great many traditional yachts. For example, ›Silver‹ would happily do 7 knots while consuming less power than a modern saloon car«.

Schwarzwalder points out that a refit will automatically reduce the impact a yacht has on the environment while replacing a 20-year-old genset with a new generation one, for instance. But he favours the option to build a new one, too. Blohm + Voss is touting an efficient 111 m vintage-look new building project to whet appetites. A refit rarely involves changes to the hull shape, except for a small stern extension perhaps, and might even mean extra displacement if the superstructure is enlarged resulting in a less efficient hull moving through the sea.

Moving materials for new buildings and refits can have a significant impact. McMullen & Wing avoid the use of teak decks (even with replanting there is a significant land use involved in growing teak) and have used granite. Selective use of materials and the avoidance of rare woods or skins is a step forward. Mark Smith of Michael Leach Design said that for their recently launched, 96-metre »Palladium« »very expensive, high-tech but eco-friendly finishes that do not harm or deplete the universe were specified«.

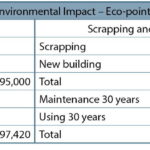

Feadship’s joint two-year research project into the environmental impact of refitting or new build made its calculations using the Eco-Indicator 99 method which allows for the aggregation of several environmental impacts, such as global warming, acidification and toxic effects into one »score«, based on the Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) methodology. Building a 70-metre yacht would have the negative environmental impact of 520,000 eco points and regular maintenance including drydocking, repainting, anodes and more results in 2,200 eco-points per year. The actual use of the yacht is estimated at 450,000 eco-points per year, which mainly consists of fuel consumption including also the impact of fuel production as its emissions. Refitting a yacht is calculated to cause 95,000 eco-points.

Balancing the aforementioned 240,000 eco-points »credit« for scrapping another boat at the same time and assuming a 30-year old yacht has 10 % higher fuel consumption and requires 10 % more maintenance, gives the result: »scrapping plus new build« works out as 185,000 eco-points more damaging than a refit at launch – but subtracting the annual saving compared to a refitted boat of 45,220 eco-points, this option beats a refit after about 4 years. The chart gives a persuasive argument to build a new super yacht.

Use: yachting and life aboard

Other than burning up fossil fuels to get from A to B – or more likely Monaco to St Tropez – the largest single impact on emission is the Heating, Ventilation and Air-Conditioning (HVAC) system, both for the new build as for the refit. This subject has come up in two of the Yacht Club de Monaco’s annual spring environmental symposia and there is certainly a movement – or at least talk of one – towards marina developers and operators playing their part by supplying electrical power at the berth, from a clean source, to avoid the use of generators. Schwarzwalder believes that marinas should eventually enforce the use of shore power, banning the running of generators, but provide it at a fair cost, rather than inflated prices, just because it is for expensive yachts. Chief stewardesses could do their part, simply by explaining the extra cost of running air-conditioning, especially out on deck.

Federico Bennewitz of Viareggio Superyachts (VSY) is an advocate of new build. All of his yachts have auxiliary diesel electric propulsion for quiet harbor use, and he believes that Life Cycle Assessments (LCAs) are not particularly useful unless something will change as a result of all the measurements and it is possible to compare competitors’ data. Bennewitz firmly believes that one significant improvement would be a global directive to reduce the sulphur content in fuel. »Presently in some cruising areas good quality fuel of under 1,000 ppm is not available – the antiparticle filters and catalyzers cannot treat over 1,000 ppm«, he says.

Liveras Yachts, owner-operators who manage the 60-metre »Andreas L« always seek out the cleanest fuel available for their charters, with the lowest sulphur content. One of their greenest charters is ironically at the Monaco Grand Prix watching the F1 cars race by – as the yachts in port do not move for 5 days!

According to VSY calculations, the production of 4,000 ekW for propulsion and 800 kW for hotel / auxiliary requirements on a 62-metre motor yacht equals the energy requirements for 1,600 apartments. Similarly, CO2 emissions for a week’s cruise equals six years use of a high-powered car. Nuclear rods and fuel cells are feasible options for the future. The problem is to take care and drop off your spent rods in the right marina recycling bin. The owner of »Ethereal« built his boat so that she could be retrofitted with fuel cells within a decade, replacing existing lithium ion batteries. Fuel cells are used extensively in German submarines and that is one area where crossover between yachting and shipping might benefit the environment.

Blohm + Voss seem to be well placed to draw on Hamburg’s enormous pool of efficient shipbuilding skills and green technology. Furthermore, they have recently been awarded Best Motor Yacht of the Year (jointly with Pichiotti / Perini Navi) with »Eclipse«. This 162.5 m super yacht has also won the award best displacement motor yacht of 3,000 GT and above. In addition, the shipyard got a Judges’ Special Award for »Palladium« at the World Superyacht Awards in May 2011.

One ship builder predicts that within 30 years all its ships will use methanol and batteries plus sails, foils and solar panels.

Designers harvesting the sun and the wind like within the Skysail system and wave energy, both on yachts and in the marina environment, and who explore the earth’s core for geothermal energy, might one day create enough power to recharge yachts in their berths. These visionaries are likely to win hearts as yacht owners, guests and charterers reassess their core values in life.

A number of owners, many of whom wish to remain anonymous, invest time and resources in research and development. In two or three decades, the new era of super yachting will most likely be much more in harmony with nature as sailing already is. Top 100 lists might then be rated according to low environmental impact rather than length. Green awards hosted in the world’s cleanest super yacht marina resort will be the event to make an entrance at, possibly in several locations simultaneously to avoid unnecessary travel.

Super yacht owners and charterers will eventually demand to be seen doing the right thing. Project managers such as Marine Construction Management (MCM), a company which exhibits at the Monaco Yacht Show 21/24 September (monacoyachtshow.com), are adding detailed sections on environmental impact to pre-contract development discussions. This also includes »green« recommendations which will be considered before owners make a final decision on builder and designer and whether to do a major refit or build new.

There are too many variables to conclude whether new build is better than a major refit for the environment, and each project needs to be evaluated on a case-by-case basis, however, »green super yachting« is here for good, even if it is an oxymoron.