Gulf of Guinea piracy is more dynamic and volatile than Somali piracy. Dirk Steffen reports on recent incidents and explains the different natures of attacks

Typical headlines found in the press since late 2012 or early 2013 are »Nigeria emerges as a center for pirate[ds_preview] attacks« or »The Gulf of Guinea: the new danger zone«. They suggest that something is afoot in the Gulf of Guinea that has not been there before. In fact, it remains the same »old« danger zone.

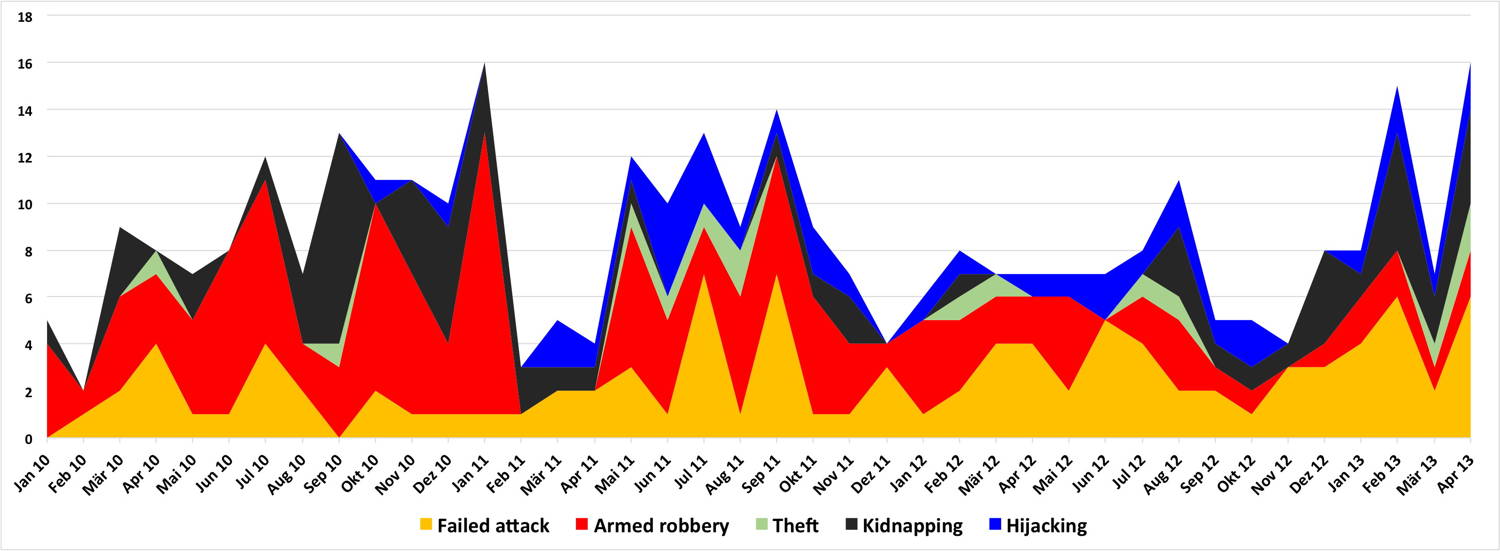

In sheer numbers, the Gulf of Guinea experienced a decline in maritime security incidents between 2008 and 2012, before this trend was reversed in early 2013. The overall decline until then was due to a reduction in offshore attacks by Nigeria’s Niger Delta militants, who accepted a government amnesty in October 2009.

Since then, the situation in Nigeria has remained fluid, but with only one qualitatively new development: the theft of cargo from hijacked products tankers, like that on 24 December 2010 when Nigeria-based criminals hijacked the products tanker »Valle Di Cordoba« and discharged part of her cargo. This was a new modus operandi pioneered by Nigerian criminals syndicates based in western Nigeria, rather than in the Niger Delta. These types of attacks gradually expanded to the west to include the waters of Ivory Coast in late 2012.

Tanker hijackings

The Nigerian hijacking modus operandi is fundamentally different to that off Somali cost. The objective is the cargo of products tankers, usually of automotive gas or diesel, which is discharged into bunker barges during those short duration of hijackings. So far 85 tankers have been attacked in the Gulf of Guinea between 24 December 2010 and 30 April 2013. Of those, 29 were hijacked (some including cargo theft ranging between 1,000 and 5,000 mt of product) – a success rate of over 30 %, not counting the 16 armed robberies not included in that number. Numbers of attacks and successful hijackings of tankers have fallen in 2012, but the problem persists.

How did this problem come about? Fuelled by high oil prices and rising production, the Nigerian government has successfully bought off ex-militant leaders with lucrative pipeline surveillance and maritime security contracts. In return, these have »enforced« maritime security where it was convenient, even collaborating with their erstwhile foe, the Joint Task Force, to bring renegade militants to heel. This has effectively resulted in some organized criminal activities moving beyond the areas that the new maritime security contractors are obliged to secure, such as neighbouring Gulf of Guinea countries. Nigerian organized crime, with its regional network, is ideally placed to exploit the weak offshore security capabilities of those neighbouring states.

Kidnap-for-ransom attacks against general shipping

As tanker traffic became more wary, and Gulf of Guinea countries enforced safe zones for ship-to-ship transfer and anchoring to focus their limited naval patrol assets, the pace of tanker attacks slowed. Instead, kidnapping of crew members off the Niger Delta became a very public issue, when offshore kidnappings resumed in late 2012 after a hiatus of several months. It is important to point out that the perpetrators of these attacks are not the same that are behind the tanker hijackings. Niger-Delta-based offshore kidnap-for-ransom attacks are a cyclical phenomenon, reflecting local tensions and disagreements in the Niger Delta. In the past, these episodes were ended abruptly and often violently through a co-operation of government security forces and established ex-militants, such as was the case against the ex-militant leaders Commander Obese and Mammy Water in 2010 and 2011.

Historically, the kidnap-for-ransom modus operandi has been closely linked to the funding of militant groups in the Niger Delta and remains aimed primarily at oil & gas offshore and offshore support vessels in that area. This segment suffered especially during the upsurge of offshore kidnappings in 2009 and 2010. Unlike the highly organized and targeted tanker hijackings, the local militant groups have a local focus and lack the sophisticated criminal network that allows the illegal bunkering gangs to move their operations further afield. This has traditionally led them to go after the »low-hanging fruit« off their own doorstep. However, opportunistic attacks against passing merchantmen are a well-documented feature of this type of Niger-Delta-based piracy, attested by attacks such as against the »Spar Rigel«, a bulk carrier that was robbed 55 nm south of Bonny on 9 January 2012, or against the reefer »Breiz Klipper«, which suffered the abduction of three crew members near Bonny River fairway buoy on 28 February 2012.

The current phase of offshore kidnappings coincides with a period of instability in the Niger Delta that may well continue into the election year 2015. The range of the attackers, primarily to the south of the Niger Delta, has also increased perceptibly in the course of 2012. The tanker »Zouzou« was attacked 100 nm south of the Niger Delta in March 2012, but at the time this was believed to have been associated with the tanker hijackings and hence did not attract the attention it should have due to its unusual location. On 30 June 2012, a double attack against the tanker »Cap Guillaume« and the container ship »Anglia« took place 120 nm south of the Niger Delta, demarcating the furthest distance that attacks originating from Nigeria had occurred in that direction up to that point.

In early 2013 ranges crept up from 96 nm in the case of the »Esther C« (crew members abducted on 7 February 2013) to 108 nm for the »Hansa Marburg« (crew members abducted on 22 April 2013). The »Cap Theodora«, a tanker, was attacked unsuccessfully on 16 April 2013 at 150 nm off the coast. For at least two recent cases there is also evidence of the attackers using hijacked offshore support vessels as logistical platforms for launching their attacks. This is generally thought to be the case for attacks further than 35–40 nm from the coast, which is the maximum operational range for an unsupported Nigerian speed boat. This, too, is a known militant modus operandi and had in the past been used primarily against platforms and floating installations, such as against the FPSO »Bonga« in 2008. The new twist is the use of such vessels against what would appear to be opportunistic non-offshore targets and the success against such ships underway where they had failed in 2012, even at relatively high speeds of 15–18 kn.

Outlook

In order to defend against Nigerian piracy, it is essential to understand that shipping and offshore is dealing with a diverse threat within a relatively confined area, which depends on the nature of the operation. Information security is more relevant to tanker operations than it is to that of dry cargo ships which are less at risk west of Lagos. Gulf of Guinea piracy is also more dynamic and volatile than Somali piracy, less dependent on seasons and weather, more shaped by the political, criminal and community relations within the Nigerian society. This is particularly true of the kidnap-for-ransom attacks. While these attacks are unlikely to follow the tanker hijackings’ westward move, ranges of 100–150 nm to the south and southwest of the Niger Delta can be expected to become the new standard for such groups, although the risk will always remain higher for ships trading in or near the coastal waters of the Niger Delta.

Although there are not yet clear signs of a likely breakdown of the amnesty programme in the near future, there are signs that an increasing number of local factions have turned to piracy to make money in 2013. This means that offshore kidnap-for-ransom activity may increase further this year, although established militants and the security forces will likely co-operate to suppress the renegades. The Nigerian government cracked down on several alleged backers of tanker piracy in September 2012, but the business model remains profitable. Tanker attacks are thus likely to continue but may become more dispersed in search of new targets. Two attacks on Lomé roads on 5 and 9 May 2013 illustrate that the threat against tankers continues. Ghana, since having taken decisive action against illegal bunkering in 2009, is viewed with some respect by Nigerian criminals. However, the reality is that the Ghana Navy would be as overwhelmed as the neighbouring navies, were it to provide comprehensive security for hundreds of products tankers seeking refuge in Ghanaian waters.

The effectiveness of local naval forces, especially of the Nigerian Navy, against this form of crime remains limited. This is not only because it involves insiders who provide target information, but also because of the uncertain loyalties and the involvement of Nigerian military personnel in illegal bunkering and fuel theft activities. Several active and retired Nigerian naval personnel have been implicated in the criminal activities surrounding the tanker attacks.

Author: Dirk Steffen

Director of Consultancy

Risk Intelligence

ds@riskintelligence.eu

Dirk Steffen