The removal of wrecked ships has always been a complex and expensive undertaking. HANSA reviews the actual status of salvage projects which have gained notoriety. The costs of salvage operations have increased in recent years

Casualties as collisions, groundings or losses in heavy seas or due to technical or human errors have raised public awareness[ds_preview] time and time again in the history of shipping. In the past, until maybe a hundred years ago, valuable cargo of wrecks close to the coast was recovered by coastal residents. Nowadays, the environmental impact of hazardous materials is often the focus of public attention which is cargo and fuel leaking from the damaged vessel. While ship wrecks were left to the forces of nature as long as technologies for their removal did not exist, today’s salvage business is dealing with the challenging conditions of heavy shipping traffic, harsh weather conditions, strict environmental regulation and not least increasing size of ships.

Rising costs

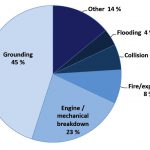

There are typically some 1,000 serious shipping casualties globally each year. Wreck removal operations have tended to become more costly in the past decade and in certain cases, costs have risen dramatically. The International Group (IG) of P&I Clubs’ Large Casualty Working Group has conducted analysis of the most expensive wreck removal operations from the past decade. The total costs of the top 20 most expensive wreck removals from the past decade have currently reached the level of 2.1 bill $ and are still increasing. Authorities in charge have proven key drivers of increasing costs. Media coverage and pressure from political and environmental groups may increase pressure on these authorities. Specific requirements, often with regard to environmental concerns, such as the approach to remove bunker fuel, may further contribute to overall costs. At the same time, technology has pushed the boundaries of what is feasible. Fuel and cargo may, for example, be recovered from a wreck lying in deep water and, if accessible, authorities will increasingly ask for this to be done.

Increasing ship size

The case of the »Costa Concordia« illustrates a number of factors which may cause costs of wreck removal to rise: a large vessel grounded at a difficult location close to the shore in a tourist destination with rocky seabed beneath deeper water. All this comes in combination with environmental concerns which require a complex and therefore expensive and lengthy solution to wreck removal. The method of choice in this case is the removal of the entire ship to avoid any pollution (the actual status of removal is to be described on the following pages).

The most notable increase in size has occured with container ships. Discharging containers is one of the decisive factors for the overall speed of dealing with a wrecked container vessel. Removing containers from a trimmed and/or listing vessel is a difficult task and takes time.

Challenge Triple-E-class

One of the most »famous« casualties in recent time was the grounding of the 3,550 TEU container vessel »Rena« at the Astrolabe Reef off New Zealand’s east coast on 5 October 2011. While removal work is still going on, the remaining containers in the bow section are currently being recovered. It seems to be a challenge to unload containers of a size class the »Rena« belongs to, and it will prove a really challenging scenario when a Triple-E-class container vessel has to be unloaded in case of emergency, as »Emma Maersk« in February this year.

The vessel took in water through her forward stern thruster as she was steaming south through the Suez Canal. Though she lost her engine power due to the flooding of the main engine room, the vessel could be berthed at Port Said Container Terminal to discharge loaded containers. A salvage team from dutch company Svitzer stopped the flooding by placing patches on the thruster tunnel. After assessment of stress and bending moments due to flooded engine room Svitzer recommended to keep the engine room flooded, also to avoid corrosion. After two weeks the ship could be towed to a shipyard in Palermo. Some 13,500 containers had to be discharged »offshore« in case »Emma Maersk« would have grounded in the Suez Canal as a result of power loss and therefore loss of manoeuvrability.