From 1913 to 2013: A century of pivotal research, innovation and progress for the maritime industry.

A review by Jürgen Friesch, Uwe Hollenbach, Peter Neumann and Christian Oestersehlte

First research institutes in Germany

From the 1880s and 1890s, imperial Germany experienced tremendous economic growth, transforming what[ds_preview] used to be a quiet and unassuming, politically fragmented patchwork of territories in the centre of Europe into one of the world’s leading industrialised countries. Merchant shipping, the navy and the shipyard industry in Germany also expanded, becoming second only to their British counterparts in the years up to 1914. Highly specialised technical and maritime expertise, building on the British model but finally taking its own directions, thus developed at many places in Germany. Technical colleges such as in Charlottenburg (1879) and Danzig (1904), as well as the German Society for Maritime Technology (STG), founded in 1899, were duly established and developed.

Yet the first German model tank basin was established inland. Ewald Bellingrath (1838–1903), founder of Elbe Schifffahrtsgesellschaft »Kette« (1868), commissioned the construction of a model basin (63 x 5/ 8 x 1.38 m) up to 1892 at the shipping line’s own shipyard in Übigau near Dresden. In addition to serving the company’s own requirements, this facility was also used by the imperial navy and private shipyards from north Germany. A new model basin (88 x 6.5 x 3.6 m) with an electric towing carriage was built in 1903 with financing from Saxony. This served the shipyard as well as the Technical University of Dresden and Hydraulic Engineering Administration and remained in operation up to 1914.

The second facility owed its establishment to a mishap. The transatlantic steamship »Kaiser Friedrich« built for Norddeutscher Lloyd (NDL) at Schichau in Danzig was not accepted in 1898 because of insufficient speed. This shipyard, otherwise highly successful as builder of torpedo boats and merchant vessels, had namely made a miscalculation with the design. On the other hand, the rival design of the fast steamship »Kaiser Wilhelm der Große« from Vulcan in Stettin had met all the requirements in 1897. The naval architect Johann Schütte (1873–1940), a teacher at the Technical University of Danzig from 1904, was commissioned to carry out more exact studies. At his suggestion, and based on the facility in La Spezia, a research institute belonging to NDL with a basin (164 x 6 x 3.70 m) was established at a cost of approximately 500,000 Marks in Bremerhaven, in 1899–1900, in a half-timbered hall, where paraffin models were towed. The plant was later demolished to make way for a port extension in 1914.

The imperial German capital Berlin formed the hub of an extensive inland waterway network – which it still does up to the present day – and after 1871 also became the location of important institutions such as the Imperial Naval Office (Reichsmarineamt) and at that time, Germanischer Lloyd (GL), now based in Hamburg. The Berlin Model Basin (Versuchsanstalt für Wasserbau und Schiffbau/VWS) was founded in 1903 and paraffin models were towed in the 150 x 6 x 3.5 m basin, which the imperial navy, that had three own shipyards in Danzig, Kiel and Wilhelmshaven, soon emulated.

Its technical department also employed a number of naval construction surveying officials in the imperial naval office, which often prescribed detailed designs for the shipbuilders and its own model basin (45 x 15 x 5 m) established in Berlin-Lichtenrade from 1906 therefore represented an appropriate supplement to its range of capabilities.

Private initiative and state promotion – HSVA’s birth

Hamburg as the largest German port with its impressive cluster of prestigious shipping lines and shipyards finally became the location of the leading German ship model basin. Prof. Friedrich Ahlborn (1858–1937), who taught at a secondary school with a focus on mathematics and science and occupied himself with flow research in his leisure time, finally submitted to the Senate of Hamburg an application for the financing of a 35 m long glass model basin in 1904. This proposal was not approved, but the idea was not forgotten. Its breakthrough was promoted in particular by the shipyard Blohm+Voss and its founder Hermann Blohm (1848–1930).

At this juncture, mention must be made of the naval architect Dr. Ernst Foerster (1876–1955), who was employed at Blohm+Voss between 1903 and 1912, finally as chief designer for merchant shipbuilding. He played a crucial role in the design of the passenger ships »Cap Finisterre« (1911), »Cap Polonio« (1914), »Vaterland« (1914) and »Bismarck« (1914/22). In 1912, the director general of Hapag, Albert Ballin (1857–1918), appointed Foerster director of shipbuilding at the major Hamburg shipping line and gave him power of attorney.

Foerster recommended the construction of a tank of much larger dimensions (200 x 15 x 6.7–7.25 m) at an estimated cost of 1.35 mill. Marks. An eight-man commission of the Hamburg Chamber of Commerce comprising renown shipbuilding experts approved Foerster’s proposals in 1910, but included some modifications. In November 1912, the tax department approved the estimated construction costs by the State of Hamburg. And in 1913, the Hamburg Senate decided to build the research institute on state property with public funds.

The new facility, the Hamburg Ship Model Basin (HSVA), was established on the occasion of the first shareholders’ meeting on 7 June 1913 as a GmbH (private company). The shareholders comprised a total of 16 German shipyards as well as the Hamburg-based shipping lines Deutsch-Austral, DDG Kosmos, Deutsche Ost-Afrika-Linie, Hapag, Hamburg-Süd and Woermann.

Building of the facility

The facility was built on Schlicksweg 21 in Hamburg-Barmbek from 1913–15 according to the plans of Foerster and with substantial support from Hermann Blohm. The company Dyckerhoff & Wiedmann experienced in concrete construction was commissioned to build an overall 350 m long channel-shaped basin, the main part being more than 150 m long, 8 m wide and 4.5 m deep with the remaining 200 m being 16 m wide and 6.75 m deep. Two of the electrically operated towing carriages (weight 23/13 t, 88/44 hp), produced by MAN in Gustavsburg, could tow the models (8–10 m/s and 5 m/s), but in the planning it was envisaged from the start that testing freely operating models with their own propulsion should also be possible.

In contrast to the institutes in Dresden and Berlin, which had been promoted by inland shipping and the navy, the HSVA owed its creation to German ocean merchant shipping and the shipbuilding industry. Unlike the short-lived Bremerhaven facility backed only by one German major shipping line, the model basin in Hamburg enjoyed more broadly based support.

The actual challenge for the still very young HSVA came only after the end of the war, when there was a severe slump in orders. It was even considered closing the facility in 1919. Contacts in the Netherlands then led at least to some work.

As a result of the terms of the Versailles Treaty, which in 1919 envisaged the handing over of German merchant ships of over 1,600 gt, the German merchant fleet had to be reestablished. Shipping lines succeeded in buying back some vessels handed over to the Allies, and German shipyards with their plant and equipment dating from the Wilhelmine era, but at that time still relatively modern, were able to devote themselves to newbuilding activities.

The restoration of a German merchant fleet capable of competing with shipping volumes of the former enemies presupposed availability of state-of-the-art shipbuilding expertise. This was where HSVA’s chance lay.

International reputation

In 1926, a quarter of the orders came from abroad, half from German ocean shipping and another quarter from inland shipping. The latter led to the construction of a special shallow water basin (150 x 3.14 x 0.3 m). The technical development at that time was also reflected in 1925 in the assumption of tests with hydroplanes and aircraft floats, which were annually subsidised with 15,000 Reichmarks by the central government transport ministry.

While he energetically promoted the expansion of the HSVA, director Günther Kempf (1885–1961) expanded contacts with colleagues at research institutes outside Germany. This initially yielded the practical benefit that the HSVA’s own results in the tanks in Britain as well as Washington, Paris and La Spezia could be confirmed and their precision optimised.

Finally, Kempf invited his foreign colleagues in May 1932 to attend a specialist conference on hydromechanical ship propulsion in Hamburg. Subsequent meetings were held in The Hague in 1933, London in 1934, Paris in 1935 and Berlin in 1937. The war prevented a further conference being held in Rome. These meetings finally developed into the International Towing Tank Conference (ITTC), which now takes place every three years.

A constantly increasing amount of testing work – initially unaffected by the world economic crisis following »Black Friday« in 1929 – led in 1930 to the construction of a special model basin (320 x 5 x 2.5 m) for hydroplanes and aircraft floats, which could be tested with a high speed of max. 20 m/sec. The economic crisis led initially to further orders for the more streamlined and thus less costly optimisation of inland waterway vessels. Studies on the ship hull form (1931), propeller cavitation (1933) as well as wake measurements (1935/36) were carried out for the French fast steamship »Normandie« (1935). In 1932, the Soviet Union ordered a cavitation tunnel, which was delivered to Leningrad in August 1933.

Under the National Socialist regime

The upturn in the late 1930s with the gradual recovery of the world economy involved in Germany rearmament carried out under the National Socialist regime. This acted like a gigantic job creation programme. The staff at the HSVA increased from 68 to about 120 employees between 1934 and 1939.

In 1939, Hermann Lerbs (1900–68) was appointed Kempf’s deputy in order to reduce the latter’s work load. 1,480 test series with 175 complete and 62 partial models and 228 model propellers were carried out between 1938 and 1939. The HSVA had published 200 reports since 1919. The work volume required the construction of a new office extension on the east side of the model basin hall.

International contacts were maintained and expanded also at that time. On the occasion of the 25th anniversary of the HSVA, Kempf invited 230 delegates from 22 countries to a lecture event on »Hydromechanical problems of the ship propulsion system«. Probably more or less notwithstanding the deteriorating general situation due to the politics of the National Socialist regime, the international reputation of the HSVA and its director that had been well-earned by specialist technical work, was undoubtedly evident at this event before the Second World War made a completely new start necessary.

HSVA in the Second World War

Owing to war requirements, military orders dominated from 1940. According to a rough estimate, about 70 % were for the navy (including fast patrol boats from Lürssen), 20 % for the air force and 10 % for inland shipping. As a result of his scientific work, Kempf was appointed professor in 1942 and the same year saw the beginning of the testing of the strength of original size aircraft parts in the model basin, which necessitated a lengthening to 450 m and the installation of a new 100 t towing carriage with an output of 2,000 hp. The manoeuvring basin was also expanded in 1943 (diameter 100 m, depth 3 m) and used above all by the navy.

The devastating air raids on Hamburg with massive use of incendiaries at the end of July 1943 caused extensive destruction also at the HSVA. The model workshop and the office premises burnt down and the halls were damaged. Half of the personnel (affecting 60 families) were bombed out and then housed in 18 makeshift dwellings grouped around the manoeuvring basin, as well as in other accommodations.

Beginning anew after 1945

On 3 May 1945, British forces occupied Hamburg, which was assigned to the British zone of occupation and, despite widespread destruction, became the important supply port for British units stationed in north Germany. There was a final rallying speech on 7 May and Kempf’s message still reflected former attitudes. He confirmed the defeat and expressed the hope for a »united Europe with Germany participating as a partner with equal rights« as well as wishing further employment, he claimed Hitler’s »outstanding and lasting achievement is that he formulated a leading political idea in the uniting of national ideals with socialist ideals …«

But the contents of his speech were quickly overtaken by events. Half the personnel had to be dismissed already on 31 May and the other half in August. The HSVA, which, with its facilities had already attracted the interest of British and American experts, was closed on 23 July 1945.

The new cavitation tunnel completed in the war was dismantled and shipped for reassembly to England. After destruction of the model tank facilities, the buildings of the HSVA were later used for storage purposes. Technical documents stored privately at the homes of employees in expectation of the end of the war were returned to the facility with the hope of continuing work in May 1945 and were seized by the British authorities and taken away. The present archives thus begin again only in the post-war period.

Start of the »Wirtschaftswunder«

After 1945, German shipping and German shipbuilding were initially subject to rigorous restrictions. Shipping remained for a number of years at first limited to coastal shipping and fisheries, which were vital for nutrition in starving post-war Germany. The yards also had to keep themselves going with all forms of activities unrelated to shipbuilding and repairs before new buildings were permitted in 1948/49. The last restrictions on shipbuilding and shipping were removed in 1951, and the introduction of the black-red-gold merchant flag of the Federal Republic of Germany in the same year, instead of the C-Pennant of the occupation period, marked a symbolic conclusion of the latter and the start of the West German »Wirtschaftswunder« from the mid-1950s.

Up to then, years of uncertainty and provisional arrangements had to be endured, also by employees of the former HSVA. After using an emergency shelter at Rothenbaumchaussee 83 between July 1945 and May 1946, 17 remaining employees, including Kempf and Lerbs, joined to form a »Hanseatic Engineers Association« (HIV) in 1946 at the company H. Maihak AG.

On 17 September 1946, in the context of the denazification process, Kempf was classified as »unobjectionable«, and in the statement of grounds it was noted without providing more exact details: »… politically unobtrusive. Greatest commitment on behalf of politically and racially handicapped«. At the same time, Lerbs, on record as being »party opponent« and »anti-Nazi«, received the same classification.The denazification of Foerster proved to be a more complicated procedure, despite his problems with the National Socialist regime. On 9 May 1946, the meanwhile nearly 70-year-old Foerster was excluded from all professional activity. After one and a half years, reports that had incriminated him proved to be dubious, so in October 1947 the proceedings were ordered to be resumed, which led to the lifting of all professional restrictions. A contributory factor was that the First Mayor of Hamburg, Max Brauer, who had known Foerster from the years before 1933 and met his brother in American exile, had put in a good word for Foerster.

Reestablishment of the facility

A working plan compiled under the authority of the HSVA in December 1947 refers to a 16-man working group concerning itself with, for example, lectures, publications, expert’s reports and production of teaching aids for instruction in shipbuilding. Also foreign contacts were reactivated and maintained. With the approval of the Hamburg school authority and under the supervision of the occupying power, between 1947 and 1953 the remaining core of the HSVA personnel could study simpler research problems concerning the steering and vibration behaviour of ships in the shipbuilding laboratory of the engineering school at Berliner Tor, where a basin (30 m) was available. The occupying power strictly supervised test activities, which had to be approved.

A plan of a »shipbuilding institute for Hamburg« with a model basin is dated 21 October 1949 and bears the signature of Kempf. The Allied occupying powers issued a formal work permit at the beginning of April 1951. The HIV as provisional arrangement was dissolved. As it was no longer possible to revert to the old site, the construction of a new model tank basin with modern facilities was begun on 22 February 1952 on the site of the former Barmbek Schützenhof at the address still valid today (Bramfelder Straße 164), incidentally not very far from the former facility on Schlicksweg. The HSVA was reestablished with financial support from the federal government as well as the coastal states Hamburg, Bremen and Schleswig-Holstein.

Initially, a model basin (80 x 5 x 3 m), an adjoining manoeuvring basin with a rotating arm unit (25 m diameter, 3 m deep) and a shallow water basin with circulating flow (80 x 3.8 x 0.8 m) were set up. The workshops and the main building were put into operation in 1953–54. The HSVA as an important scientific institution could thus again support the German shipbuilding industry, which experienced a boom in the 1950s.

Kempf headed the HSVA for a few more years and then went into retirement at the Walchensee in Bavaria. He was presented with the Grand Federal Cross of Merit

in December 1955. Lerbs was appointed Kempf’s successor in November 1955. He was well prepared for this appointment with his activity as second manager from 1939–47. In July 1955, he was appointed full professor at the Institute for Shipbuilding of the University of Hamburg, having had to turn down another offer from the University of California, Berkeley. In the meantime, Lerbs had already been able to work in Haslar in 1948 and at the David Taylor Model Basin in Washington serving the U.S. Navy in 1952.

The putting into operation of a cavitation tunnel in 1954 was followed by a second model basin (200 x 18 x 6 m) in November 1957. Engineering advances in the field of ice-breaking technology began in the 1950s. The first ice-breaking steamship was built in 1871 in Hamburg. The further development of this type of vessel proceeded in line with general shipbuilding technology, but for decades the ice-breaking process could be optimised only with an experience-based approach.

After the HSVA had carried out large-scale tests with the icebreaker »Emshörn« on Lake Mälar in Sweden in 1955, it installed its own small ice model basin (measuring approximately 8 x 1.8 x 1 m) on the inner court in 1958. The large model basin was equipped with a wave maker in 1958, and a large cavitation tunnel (diameter 75 cm) was built in 1960.

With its maximum speed of 20m/s, this tunnel is even today one of the outstanding model basin facilities of its type and is essential for basic research. The reestablishment of the HSVA was thus completed after the war.

Fresh challenges

Although the West German post-war boom more or less continued up to the first oil crisis in 1973, the shipbuilding industry on the North Sea and Baltic gradually came under pressure from East Asian competition. The bankruptcy of Schlieker-Werft in Hamburg in 1962 was just the first of many shipyard closures to come up to the present day, and the formation of the shipyard group HDW from several companies in Hamburg and Kiel in 1967 was only one example of a concentration process involving a massive reduction in quantitative capacities, particularly from the 1970s and 1980s.

The German shipbuilding industry underwent a transformation from a broadly based to a specialised niche branch. The daily work of the HSVA in areas such as cruise ships, yachts, naval vessels, and not least ice-breaking research, corresponds to the requirement in Germany to develop special-purpose ships.

While the construction of standard types of vessel, especially tankers and containerships, has now shifted to the Far East, the correct response of the German maritime sector to these challenges has remained strengthening shipbuilding research capacities as to maintain at least a qualitative positioning. The HSVA has played a vital role in this respect up to the present day.

Its 50th anniversary was celebrated on 7 and 8 September 1964 with an international specialist symposium. In 1965, the large model basin was lengthened to 300 m. This was followed in 1971 by a third cavitation tunnel (0.57 x 0.57 x 2.20 m) and a new ice tank (37 x 6 x 1.2 m) built with support from the Federal Minister for Research and Technology in 1971–72.

Electronics found its way into the measurement technology of the HSVA as early as the mid-1950s. The first computer system, a Zuse Z 31, was already put into operation in 1962. The large towing carriage has been computer-controlled since the beginning of the 1970s. The planar motion unit put into operation in 1976 is also controlled by this computer. With this test facility, very extensive and precise details on the manoeuvring behaviour of new vessels can now be obtained for the shipbuilding industry.

In the 1960s, the main principles for procedures routinely applied today for calculating ship movement in a seaway were also established by Prof. Otto Grim (1911–94). This period also saw the studies of Grim on safety against capsizing and, logically, the double flap wave maker for the simulation of regular and irregular waves went into operation in July 1980.

Ice basin and side wave maker

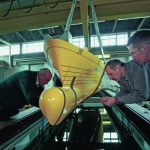

An additional ice model basin (78 x 10 x 2.5/5 m), with adjoining ice laboratory, was finally installed in 1982–1984 to enable HSVA to retain its global leadership in ice technology, and apart from HSVA. Since this time, it has been one of the three largest ice tanks in the world. The fourth cavitation tunnel, the hydrodynamics and cavitation tunnel HYKAT, went into operation 1989. With this testing facility, HSVA in turn designed one of the leading cavitation plants worldwide and introduced it into daily practice. The HYKAT has a test section with rectangular cross section of 2.8 x 1.6 m² with a length of 11 m, in which propellers can be studied in the wake, i.e. behind complete ship models up to 12.5 m long.

In 2011, a 40 m long demonstrator of a side wave maker was installed in the large model basin with the aim of studying ships not only in waves from ahead or astern, but also from the side. With this investment, HSVA adapted to the market needs with respect to safety and performance levels of ships in a seaway as requirements for studies of movements and stresses of ships in waves from all directions have been increasing considerably for many years. Such tests are indispensable for all special-purpose vessels, ferries, ro-ro vessels and cruise ships. In the offshore area, e.g. the development of offshore wind turbines, tests in waves that are as realistic as possible are essential to guarantee the safety of the plants and their installation and maintenance by special-purpose ships as well as their optimally cost-efficient operation. The City of Hamburg contributed to financing this test facility.

Apart from the elaborate tests, computational fluid dynamics (CFD), in part with a program system developed in-house, have been carried out in the last two decades. Calculations are nowadays an important means of optimising flow processes and contribute increasingly to the understanding of difficult flow conditions.

Changes in workforce and management

The development of the HSVA after its ›relaunch‹ is also reflected in its workforce. 1970 was the peak year with a staff of 146. The serious crisis in German shipping in the 1970s and 1980s, when numerous shipyards and shipping lines had to close, also affected personnel development at the HSVA. The staff declined from 141 persons in 1987 to 84 in 1994. Meanwhile the workforce has expanded slightly to 89 as of 2012.

The management of the HSVA after a vacancy following the death of Lerbs, which was filled by the head of the propeller department, Herbert Rader, was assumed in 1969 by Prof. Grim. His name cannot be separated from the upturn in shipbuilding research in Hamburg. He was involved from the beginning in the rebirth of the HSVA, working there until 1962 as head of the research department. In 1962, he was appointed successor of Georg Weinblum at the Institute for Shipbuilding. In addition to his teaching activities, he then took over the management of the HSVA from 1969–74.

Grim was succeeded by Prof. Odo Krappinger as head of the HSVA from 1975 to 1988. In 1990, he was awarded the Commander’s Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany for his internationally recognised work in the area of ship safety and for assuming overall responsibility for the designs of German research ships such as the »Polarstern« (1982), »Meteor« (1986) and »Sonne«.

After 1988, the HSVA was headed by Dr. Hans G. Payer (1988–93), Prof. Gerhard Jensen (1993–2001) and Dr. Dietrich Wittekind (2001–04). From 2004–05, Prof. Gerhard Jensen and Jürgen Friesch together headed the facility, with Friesch having been its director since 2005. Born 1950 in Esslingen in Baden-Württemberg, Friesch studied shipbuilding in Hanover and Hamburg from 1973 to 1979 and joined the HSVA in 1979. Initially active as project manager, Friesch was finally appointed head of the propeller and cavitation department before he became managing director. His focal areas are propulsors, cavitation predictions and development of cavitation test facilities, continually connected with test runs on large ships to validate the research work in the area of propeller cavitation.

From non-profit to commercial orientation

With the cuts in research funding in the 1990s, HSVA had to change from being a non-profit institution and become a much more commercially oriented service company. That this transformation has succeeded is shown in an exemplary way by the continuous flow in orders from outside Germany, especially in the last ten years. In 2012, orders from industry accounted for about 80 % of HSVA turnover, with 75 % of these coming from abroad, particularly the Far East. Partially funded research projects of the EU, the Federal Ministry for Economics and Technology and the Federal Environmental Ministry generated the remaining 20 % of total sales.

The subject of climate change has today acquired an importance both politically and socially that was scarcely foreseeable several years ago. The resulting significant opportunities for German shipbuilding lie in the areas of fuel-efficient vessels with low emission levels. Thus, the time up to the keel-laying of a new ship has to be used for optimising the hull comprehensively. Energy-efficient vessels can offer competitive advantages with lower operating costs in the long term. This potential is taken very seriously by shipping lines, as is clearly shown by the increased enquiries in the last two years particularly concerning the efficiency of shipbuilding products, for both new buildings and conversion projects. That aspect, along with all areas of transport in ice-covered waters, represents a great opportunity for the HSVA for maintaining its global position.

In its first hundred years, the HSVA has survived the dramatic ups and downs caused by historical events – two World Wars, the beginning and end of the Cold War along with a profound change in social mentality – as well as the seemingly eternal fluctuations in the fortunes of German shipping. It is entering its second century as one of the leading institutions of its type worldwide. Because of the volatility of its business, shipbuilding nowadays suffers from image problems among the public at large. But the notion that it involves an ›old industry‹ restricted to the simple bending of plates is profoundly mistaken. Rather, shipbuilding is based on a highly developed engineering science, as the HSVA certainly constantly demonstrates in its work, day by day.

ürgen Friesch, Uwe Hollenbach, Peter Neumann, Christian Oestersehlte