By end the June 2016, if all goes well, the Panama Canal – with a new set of locks – will be able to accommodate vessels wider and longer than possible previously. The maritime industry in the US adapts itself to more or less huge changes

Mr. Jose Ramon Arango, on staff at the Panama Canal Authority (ACP), explained recently that, in the early 2000s, the[ds_preview] ACP planners had developed plans for market segmentation and the implementation of a new toll scheme for time-sensitive container vessel transits. Following the expansion program’s completion, vessels of up to 14,000TEU will be able to transit the Canal. Mr. Jorge Quijano, Administrator/CEO of the Canal, speaking at the American Association of Port Authorities’ »Shifting International Trade Routes« conference, stressed the ongoing preponderance of trade flows tied to the States. He cited fiscal year 2015 data (Oct 2014 through Sept 2015) showing that 70.2%, or 160.8mill. long tons (lt), of the Canal’s overall cargo throughput (229.1mill. lt – mainly bulk cargo), either originated in, or was bound for the U.S. Of this, 82.1mill. lt represented trade between the U.S. East Coast and Asia, while flows between the U.S. East Coast and West Coast of South America accounted for 36.6mill. lt.

Changes in trade flows will occur as a result of the Canal expansion, with important impacts on cargo flow into and out of the United States, and throughout the Americas. The changes are not known with certainty, but experts have been able to construct robust scenarios of what might happen. Mr. Quijano pointed to four segments where the Canal’s position will be enhanced:

– Container moves, Asia to U.S. but also U.S. to West Coast South America

– Energy: LNG and LPG exports from Texas and Louisiana to Asia

– Potentially, crude oil flowing from Texas and Louisiana to Asia

– Potentially, larger size drybulk cargoes (coal, grain, iron ore)

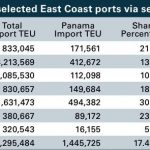

Containerized cargo

In the container trades, the carriers’ move to bigger ships created a »cascade« of smaller ships, with sizes clustered around 8,000TEU and 14,000TEU – which are set to be redeployed in existing or in new trades – including through the Canal. Mr. Quijano said that 33 container services were already transiting Panama by early 2016. He added that »The Panama Canal expects to recover the services that were redeployed thru Suez Canal and, in addition, we expect an increase of cargo diversion from West Coast ports, as soon as the new locks begin operation.« ACP data indicate that the Canal’s share of Northeast Asia to U.S. East Coast container trade dropped from 57% in 2009 to 37% in 2014, mostly representing gains for Suez. That’s the chunk that Panama hopes to gain back.Research (which includes sophisticated traffic flow models) was conducted jointly by The Boston Consulting Group and the leading forwarder C. H. Robinson; it buttresses their June 2015 report »Wide Open: How the Panama Canal Expansion is Redrawing the Logistics Map«. According to BCG, a shift of traffic to the East Coast that’s equivalent to »… building a new port roughly double the size of the ports in Savannah and Charleston …« could occur by 2020. Mr. Dustin Burke, Principal at BCG and one of the report’s authors, told HANSA that »… the shipping cost $/TEU is only a part of what we looked at, cargo flows are driven also by time considerations and other supply chain factors that shippers take into account.«

There are three pathways for containerized cargo to move from East Asia to the Eastern U.S. Boxes can:

– move into West Coast ports and then eastward overland by rail

– move into East Coast port via the Suez Canal and then into the hinterland by rail

– move into East Coast ports via Panama, and then into the hinterland by rail

According to BCG, »In 2014 about 35% of East Asia container traffic docked on the East Coast.« By 2020, there would be the potential for US East and West Coasts to have equal shares of the container trade from East Asia ultimately bound for the Eastern U.S.

The cargo moving through the East Coast is destined for huge local markets, but also for the middle of the country. The actual penetration will depend on multiple supply chain specific and macro-economic variables. Mr. Burke from BCG identified two important ones: the price of fuel, saying, »… the lower that the fuel prices are, the more diminished the advantages to an all water route are« and the price of moving a box (i.e. the $/TEU pricing). He said that analysis of this latter variable is tricky, »because, right now, many of the carriers’ prices are below their costs«; and that over the report’s five year horizon out to 2020, this situation may not endure.

The magnitude of Asian-origin cargo that will flow through the Canal (rather than through Suez, or into the U.S. West Coast and then eastward by rail) depends on combinations of the variables, grouped together by BCG into several scenarios. The diagram shows a »Battleground« region in the middle of the U.S. In scenarios favorable to Panama Canal penetration, cargo destined as far to the west as the Mississippi River might be shipped through the East Coast. In less Panama Canal friendly model simulations, cargo in the shaded area – which includes distributions hubs of Memphis, Louisville and Cincinnati, will move from Asia through West Coast ports (and then eastward overland by rail).

After evaluating numerous scenarios, BCG notes that likely winners from the widened Canal (if macro-economic and supply chain factors align) will be the New York/New Jersey port and the southeastern ports of Norfolk, Savannah and Charleston, due to »their relative proximity to the Battleground region and the attractive rail routes to major markets.« Baltimore and Miami (both of which have seen dredging and infrastructure investment) may also see gains from regional traffic. Railroads serving the East Coast might also emerge as »winners«; logisticians Flexport note that CSX and Norfolk Southern might gain more cargo.

Energy complex

The U.S. is also an important player in tanker trades that are being shaped as a result of the »Shale Revolution« – which increased U.S. production of crude oil and products (through increased refinery runs). With hydraulic fracturing, gas production also grew, leading to new liquefaction plants for LNG exports (which began from a facility at Sabine Pass, Louisiana, in early 2016). Four additional export facilities, three of which are in the Gulf of Mexico, are under construction, according to FERC, the regulator with jurisdiction over onshore terminals. Mr. Quijano’s presentation showed that, when completed, overall exports from terminals now under construction could total more than 66mill. t per year by 2020. A recent presentation from Cheniere Energy (owner of the Sabine Pass plant) suggests that 84mill. t/year of export capability could be online by 2025.

The widened Panama Canal may not see huge flows of LNG right away. The Cheniere presentation, using data drawn from consultants Wood MacKenzie, suggests that Europe (a destination for U.S. LNG exports not requiring a Canal transit) could see huge gains in LNG demand, before leveling off in 2020.

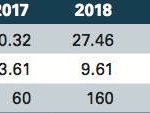

Fearnresearch, an arm of the large shipbrokerage, have provided estimates of LNG flows through the Canal. The estimates show Asia and Chile with a 35% share of U.S. exports, through 2020. If Asia takes more cargo, then the number of laden transits, with U.S. origin cargo, will increase.

Offshoots of natural gas production – LPG (propane and butane) –, associated petrochemicals, and more recently ethane have begun to move. Japanese shipping giant NYK reported that one of its Very Large Gas Carriers (VLGC), with dimensions too wide for the »old« Canal, would be one of the first vessels using a slot reservation system available for optimizing transits through the widened waterway.

U.S. exports of crude oil, opened up by the Obama administration in late 2015 after a 40 year ban, are a wildcard. There have been a handful of test cargoes, even though U.S. oil became relatively less attractive in 2015 and 2016, as its price advantage compared to other grades in world markets has narrowed.

Potential flows

Mr. Quijano also hinted at flows of U.S. crude oil to Asia, and U.S and Colombian coal to Asia, and at cargoes of iron ore from South America out to Asia. Such cargoes may be experimental and opportunistic and, initially, do not lend themselves to reliable forecasts. The shipping community’s eyes are on the widened Canal; but, everyone should remember a point made to HANSA by BCG’s Mr. Burke: »The cargo shippers will look at total cost, and bigger logistical chains, for example, where does the manufacturing take place; the water leg is an important part, but not the only link in such chains. In the long term, shipping conforms to support global supply chains, not the other way around.«

Barry Parker