Since 2019, the Flemish ports (Port of Antwerp-Bruges, North Sea Port and Port of Oostende) have a common policy on underwater cleaning, more specifically, a policy for reactive cleaning with capture. Here they present lessons learned and future challenges

This common policy arose from the commitment as ports to reconcile economic, [ds_preview]social and ecological interests in a sustainable manner. As pioneers, the Flemish ports want to give innovative companies a chance to offer a robust solution to the fouling problem that has been troubling shipping for a long time. Of course, it is also vital that ports do not ignore their responsibility regarding water quality and the possible spread of alien invasive species. Key issue is how to maintain the balance between innovation and protection of the aquatic environment. Which framework provides sufficient flexibility and perspective, but at the same time is strict enough to allow proper monitoring and enforcement? And crucial: what is the role of ports in the development and implementation of this framework? At least they hope to inspire others, because they believe we need courageous doers to act now for a better future.

What have they learned?

The Flemish ports have almost four years of experience with their framework. They still believe in their approach where they also attach great importance to feasibility. However, as expected, there are also many things that can still be improved and some new developments that need to be added. Since 2019, about 120 hull cleanings and some 280 propeller polishing operations have been carried out. Good numbers but below original expectations, partly because of the impact of the COVID-19 crisis.

To monitor the development of this technology, the ports keep in close contact with the sector. Are there new companies that sign up, do existing companies continue to offer the services or do they expand their services? It is noticeable that small companies find it difficult to reserve a spot for themselves in the hull cleaning market. Not only the purchase and development of the equipment appears to be a major investment, but the fear of not passing the test and seeing their investment end in »no result« is a show-stopper as well. So for the time being, there are still only two operators offering these services in the Flemish ports.

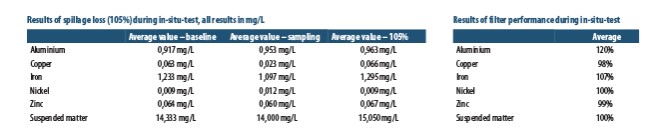

For propeller polishing, there is a lot of interest from local diving companies. The investment costs are a lot lower than for hull cleaning and that is why many are taking a chance. However, this does not always have a good outcome. Both in terms of suction and filtration performance, the Flemish ports keep finding problems during the test procedure. However, they are considering imposing a minimum filter standard, for example, the effluent may not contain any particles larger than 0.5 microns.

International standard: It’s crucial

The biggest challenge within the subject of underwater cleaning is, according to the Flemish ports, the fragmented policy. Due to the absence of an international standard, there is not only a lack of a level playing field but there is also uncertainty for all parties involved. The ports often have the feeling: Are we doing the right thing? They are convinced that this also slows down other ports in their commitment to develop regulations for these applications.

As Flemish ports, they support the notion that if the environmental regulations for underwater cleaning are well crafted, more innovation will come, and the environmental impact would be reduced, enhancing the profitability of the innovating company. By minimising uncertainty, maximising opportunities for innovation and constantly raising the standard, the greatest benefits will be achieved in both environmental and economic terms.

In the near future there will be a need to unite the forces of the existing initiatives to publish a fully supported international standard on underwater cleaning. The purpose of this standard should be at least to:

- Define the boundaries of reactive and proactive cleaning in a clear and thoughtful way, taking into account the interests of all stakeholders involved.

- Assure regulatory authorities that no damage is caused to the aquatic environment for which they are responsible. In order to remove all doubt, this requires a well-founded scientific foundation.

- Allow innovative companies to develop their solutions and commercial activities. For this purpose, it is necessary to describe a clear framework for testing and verifying the applications.

- Convince shipowners and operators of the benefits of underwater cleaning and by extension good biofouling management. The benefits gained from following the standard should be documented to inspire others.

Pro-active cleaning: The holy grail?

In addition to reactive cleaning, there is now also the development of proactive cleaning. Since ports want nothing more than to receive the »cleanest« ships, you would expect them to welcome this new development? However, there are not only advantages but also challenges.

With reactive cleaning, there was always a need to capture what was removed. With proactive cleaning, the intention is precisely to avoid the development of harmful organisms on the hull by means of regular cleaning. In this case, there is no need for capture. Ports therefore often wonder: to what level is it acceptable to clean a ship’s hull without capture? Or is it wrong to state that proactive cleaning is always possible without capture?

Some additional concerns

When the boundary between reactive and proactive cleaning has been established, a system must be developed to check the requirements in an objective way, also taking into account the spatial variation of biofouling rates all over the ship’s hull. If this assessment is not carried out correctly, there is a high risk of harm to the local aquatic environment. This method must also be verifiable by the regulatory authorities, otherwise it will be impossible to monitor these operations correctly.

Besides the release of organisms, regulatory authorities as ports are also concerned about the possible release of biocides and paint particles (seen as microplastics). These can have an impact on the local marine environment, but also cause local soil pollution. How can we be sure as ports which coatings are suitable for proactive cleaning? And what is the role of the manufacturers of these coatings?

Authors: Jasper Cornelis, Luc Van Espen (both Port of Antwerp-Bruges) and Jean-Pierre Maas (North Sea Port)

This article is a shortened version of the paper presented at this year’s expert conference PortPIC in Hamburg