While new solutions for ballast water treatment are constantly being developed, uniform standards in the regulatory field do not exist yet.

This combination bears some risks.

More or less strict regulations on testing and efficiency of ballast water treatment systems, different definitions and a lack of[ds_preview] clarity concerning requirements for the sampling and analysis of ballast water irritate shipowners. Meanwhile manufacturers are coming up with new disinfection technologies but cannot guarantee their systems will be type approved by all authorities. While most stick to the IMO regulations, the U.S. Coast Guard (USCG) has stricter rules of its own.

This area of conflict was the subject of the 4th Ballast Water Symposium by the German Shipowners’ Association (VDR), MARIKO and Bureau Veritas (BV). The main focus of the conference held recently in Hamburg was »the choice between the plague and cholera«. The provoking title was intended to emphasize the risk which shipowners have to take when they decide in favor of a certain ballast water management system (BWMS), VDR Marine Director Wolfgang Hintzsche said.

The USCG’s regulations, in force since 2013, are creating confusion among the industry. Shipping companies which trade in U.S. waters need to comply not only with the USCG’s but also with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) rules. In addition to the type approval following IMO standards, BWMS have to be type approved separately by the USCG. Since there are no such type approvals for foreign BWMS to date, the systems need an alternative management system (AMS) certificate of acceptance (HANSA March 2015 pp. 32–41).

Jon Stewart, founder of the consultancy IMTCI, clarifies on behalf of the USCG: »An AMS is neither a guarantee nor a help for a later type approval by the Coast Guard.« AMS is only a bridging solution, as long as there are no USCG approvals for foreign systems. Once there is, there will also be no more AMS. »To get an extension then, a shipowner will have to document very well why he still cannot comply.«

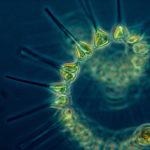

The wide range of ballast water management systems (BWMS) on the market is not making the whole thing easier. There are systems using physical disinfection via ultrasound, cavitation or inert gas. Others are based on so-called active substances, chemicals which are added or generated from the ballast water itself by electrolysis. Moreover, the salinity of varying water types differs quite a bit. There is sea water, brackish water and fresh water. Water from estuaries may also carry particulate matter. The latter can lead to a less efficient disinfection through ultraviolet light, by affecting the water’s transmissibility. Electro-chlorination needs a certain minimum amount of salt to work. So, there remain some questions such as: does that particular system work for all water types? If not, does it work in the waters the ship operates in? What happens in case the ship is deployed on other routes?

A question of definition

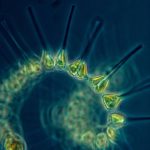

One crucial point between the IMO’s and the USCG’s regulations is the definition of disinfected ballast water. While the IMO asks whether an organism is »viable« after treatment, USCG differentiates between »live and dead«. This poses problems on the manufacturers of systems using UV-light. The radiation does not kill but damages the DNA so organisms become unable to reproduce. In the view of the industry, this means that an organism is not invasive anymore. Stewart emphasizes that the USCG has no preference for one system or technology over an other. The Coast Guard will decide individually after conducting all the neccessary tests.

So shipowners have to deal with the uncertainty for the moment, whether the system they decide for will be approved everywhere. One of them puts it straight: »As a shipowner I do not care what exactly is going on inside my ballast water treatment system.« He would be much more interested in what will happen in case of a port state control. Who will be held liable for a system failure? How often will there be controls? For how long will the ship have to stay in port? Will controls only affect paperwork and plans or will the ballast water be sampled each time, too?

The latter does not seem to be a feasable option since it would mean an immense workload and require scientific personnel for the port authorities. Susanne Heitmüller of the Federal Maritime and Hydrographic Agency of Germany (BSH) tries to soothe the shipowners’s nerves: »You have to see such controls as a step-by-step procedure with the sampling of the actual ballast water at its very end.« Only if discrepancies occur beforehand, this measure would be taken.

However, the question of best practices for the ballast water sampling and analysis are not clarified yet. Various methods are currently analyzed by the BSH. The various watertypes from different ports as well as residue of older ballast water in the tanks are a technical challenge also for the analysing process. Even the sampling itself is not trivial, Stephan Gollasch explains. The biologist is testing the sampling methods on behalf of BSH. Depending on what is being testet – salinity or organisms – only very little or a whole lot of water have to be analyzed. This consumes time and involves equipment. Also some organisms do not evenly spread in the water but form clouds. Others cannot be found in the same concentration at any time. »There are methods and equipment to efficiently conduct a sampling. But you have to choose the right one,« he says.

No international convention yet

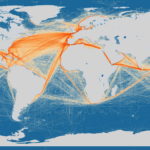

Currently shipowners have to deal with 16 local and five regional ballast water regulations. The ratification of the IMO Ballast Water Convention (BWMC), that would make the installation of BWMS mandatory globally, is not finalized, yet. The paper was adopted in 2004, but still important signers are missing. The convention will not become effective, unless at least 30 states representing together 35% of the world’s gross tonnage, ratified it. To date 44 countries signed the treaty, but they only represent 32.86% of the global tonnage. »The signature of one flag state like China, Greece, Bahamas, Malta, Singapore, Hong Kong ore Panama would suffice to bring the BWMC into force,« Ramona Zettelmaier of classification society BV explains.

There are several reasons why many states take so long to ratify the convention: Zettelmaier names factors such as costs, political will, and an insufficient number of certified test laboratories for the BWM systems. Furthermore, the lack of associated guidelines and of standards for controls and analysis are a drag, as well as the unsatisfactory capacity for the installation of BWMS.

In case the IMO convention comes into force in the near future – 12 months after final ratification, at the earliest in 2017 – the effective schedule would have to be revised, the BV representative explains. In the short time remaining, shipowners will hardly be able to install systems on all their ships that have to comply. »Technically that is just not viable,« Zettelmaier says. The industry will have to ask for a »period of grace« to comply.

Felix Selzer