Pollution, work-related casualties and health hazards in recycling yards point to a need for improvement in safety and sustainability. Two experts of DNV GL explain how the EU’s regulations aim to achieve this and the changes shipowners and recycling facilities need to prepare for

Ninety-five percent of a ship’s components live on when it is sent to die. Every year up to 1,500[ds_preview] ships are recycled to rejuvenate the world fleet and regain valuable secondary resources such as steel, aluminium and copper. The majority of these vessels are recycled in Asian countries such as India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and China, with a smaller share in Turkey. The conditions under which recycling facilities dismantle the vessels vary. Depending on the yard, basic equipment such as helmets, shoes, protective gloves and masks are not provided to all workers. Hazardous materials such as heavy metals and fuel oils leak into the surf and the soil, polluting the area and creating serious health hazards for people working on site.

While there have been efforts to regulate the handling and disposal of hazardous materials (Basel Convention 1989) and improve safety and environmental standards in ship recycling facilities (Hong Kong Convention for the Safe and Environmentally Sound Recycling of Ships 2009), they have proven to be difficult to enforce. The Hong Kong Convention has only been ratified by three countries and is not expected to enter into force before 2020, eleven years after it was adopted by the International Maritime Organisation. »Progress has been very slow until now. But the implementation of the European Ship Recycling Regulation will bring about some radical changes over the next few years. Of the roughly 60,000 ships worldwide, about two thirds are affected by it,« says Gerhard Aulbert, Global Head of Practice Ship Recycling at DNV GL – Maritime. The European Ship Recycling Regulation, in force since 30 December 2013, addresses the environmental and health issues associated with ship recycling while avoiding unnecessary economic burdens. Applicable to all EU-flagged vessels as well as non-EU-flagged ships calling at or anchoring in ports within the EZ, it accelerates implementation of the requirements of the Hong Kong Convention and sets out responsibilities for shipowners and recycling facilities both within the EU and in other countries.

Procedures need to be improved

One of the cornerstones of the regulation is the so-called inventory of hazardous materials (IHM). Every EU-flagged newbuild has to carry an inventory of all hazardous materials contained in its structure or equipment with Statement of Compliance at the earliest by 31 December 2015 and at the latest by 31 December 2018. If the ship is to be recycled the IHM should be on board from the date when the European list of ship recycling facilities is published, which is expected to happen by the end of 2016. »One thing that remains poorly defined and may differ significantly from case to case is the way in which hazardous material experts develop the IHMs,« writes Thomas Nigl, who investigated IHM standards in his master’s thesis at DNV GL. Nigl analysed the procedures in place to develop IHMs on different ships and surveyed stakeholders in the value chain, including suppliers, cash buyers, shipowners, hazardous material experts, port authorities, classification societies and shipyards, amongst others. The results of his study show that though IHMs can be considered as an important step towards establishing safer and more environmentally friendly methods of ship recycling, much needs to be improved in terms of procedures. »Methodological divergences in the development of IHMs between newly built and existing ships have led to considerable differences in the amounts of HazMats found on board«, Nigl writes. Statistical modelling also revealed that the individual HazMat expert compiling the IHM and the age of the respective ship are the most influential factors affecting the amount of HazMats found on board of existing ships. However, the factors that influence newly built ships currently remain unclear. »The industry needs definitions and documentation for the development of IHMs and the materials themselves. Standards and an effective control mechanism for material declarations in the supply chain would also be desirable to ensure that the IHM is effective,« Nigl explains. While shipowners and yards will have to take stock of what kind of substances their operating vessels or newbuildings contain, ship recycling facilities that aim to attract EU-flagged customers will have to be upgraded.

The next corner stone of the EU-regulation is a new benchmarking system. In the future, recycling will only be permitted to take place at facilities that have been approved of by the European Union. »This kind of ranking will change the face of ship recycling, as methods such as beaching will most likely be banned and recycling facilities will have to compete for European-flagged vessels by making it onto a kind of green list,« explains Aulbert. Waste disposal management, the facility’s infrastructure, safety procedures and training are some of the key factors which will determine whether recycling facilities make the cut. Some changes would be relatively easy to make, says Aulbert. In the case of asbestos this would simply be a matter of training and equipment. The mineral is not toxic to the environment as such, but as breathing in asbestos fibres can cause respiratory illnesses, it needs to be covered up in a designated rubbish facility. Substances such as CFC (Chlorofluorocarbon) that contribute to the depletion of the ozone layer are more of a challenge in areas with a very basic waste management infrastructure. CFC needs to be disposed of in incineration plants, which often do not exist near ship recycling facilities.

To reduce pollution through leakages, recycling facilities need to dismantle vessels on paved surfaces and install drainage systems to clean the site. This could prove to be a challenge in places such as Alang, where more than half of the ships that get scrapped every year end up, where high tides and a natural slope on the beach make it easy to haul ships onto the shore and carry out pre-cleaning and block breaking in shallow water. »These kinds of practices cannot continue. If recycling facilities wanted to continue beaching vessels in the future, they would need to work with pontoons, using a crane to lift parts that are broken off the ship onto pontoons and bring them to shore. This is very arduous compared to current operations. As a result of that I expect the number of recycling yards will decrease, because beaching will not prevail in the long run,« says Aulbert. Some ship recyclers have already upgraded their facilities, in order to achieve compliance with the EU regulation and gain a competitive advantage once the benchmarking system has been established. »But most recycling facilities still violate the Basel Convention’s standards for disposing of hazardous materials and have a long way to go.« Several owners are also taking steps to improve the sustainability record of their recycled vessels. »Hapag-Lloyd is one of the shipping companies that have taken the initiative to improve the sustainability of their fleet by developing IHMs for their newbuildings. But in the rest of the market progress is slow. So far, only 10% of ships that get recycled today have an inventory of hazardous materials on board,« Aulbert explains.

What does sustainable ship recycling cost?

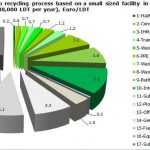

More sustainable practices are expected to increase the costs of ship recycling. Looking at an example in a Turkish yard, DNV GL estimates the average cost of breaking a ship according to the EU regulations at about 46€ per LDT (light displacement ton). LDT stands for the weight of a ship without anything on board and is used to determine the value of a ship which is to be scrapped. The most significant cost factors contributing to the price calculations include: pre-cleaning work, monitoring, IHM preparation, training, transport, storage and disposal of wastes, personal protection equipment (PPE), buildings and impermeable floor as well as intertidal zone measurements. They result in additional costs of about 17€ per LDT. In Asia, many ships are currently being recycled for as little as 20 to 30€ per LDT. Aulbert points out that while the number of yards is expected to decrease in the long run, shipowners could profit from the regulation: »I think we will see more of a division between the practice of recycling itself and the sale of recycled materials.« At the moment this is often still done by one and the same facility and shipowners often choose one that will fetch them a higher price for the recycled steel. The EU regulation allows shipowners to have a vessel recycled by one facility but sell their steel globally. »This makes owners more independent from recycling facilities regarding the profit from the ship,« Aulbert adds. »The list of EU-vetted facilities will shipowners also give a better basis for deciding which recycling yard to use and can ensure that their vessels are scrapped in a sustainable way.«

Author: Gerhard Aulbert,

Global Head of Practice Ship Recycling, DNV GL – Maritime,

gerhard.aulbert@dnvgl.com

Gerhard Aulbert