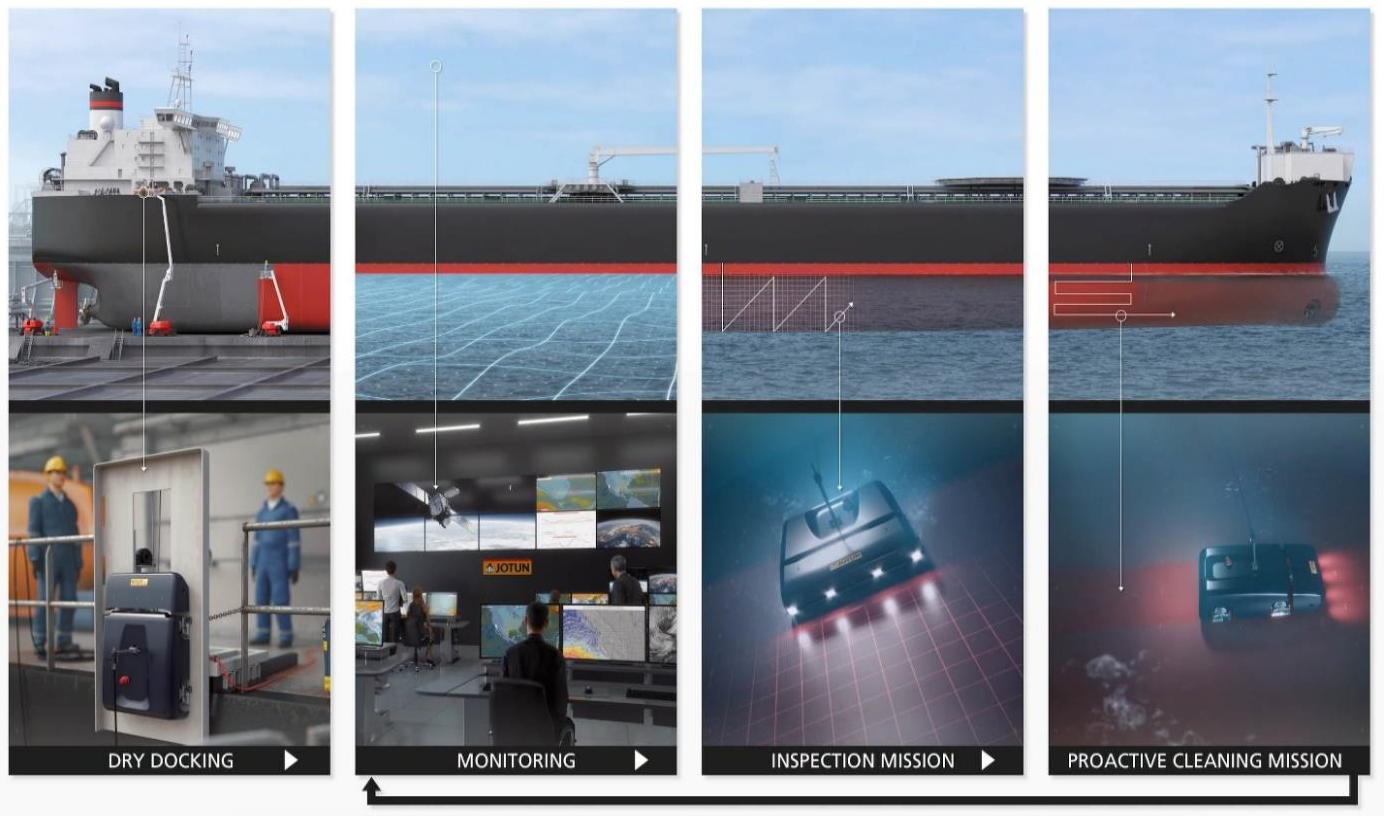

Together with a number of partners, the Norwegian coating specialist Jotun launched the robotics solution »HullSkater« in spring 2020. In the meantime, the experts are driving forward the development of guidelines in the absence of global regulation

The solution is said to combine antifouling, proactive condition monitoring, inspection and proactive cleaning as well as remote operation from[ds_preview] shore (HANSA 04/2020). »The idea of proactive measures is to capture the fouling so that a collection of waste is not even necessary. Therefore it is so important to get a global definition of proactive hull cleaning,« Alexander Enström, Hamburg-based Global Sales Director at Jotun, tells HANSA during the recent expert conference PortPIC in Hamburg.

100% contentious cleaning may not be realistic, he states, but proactive cleaning definitely is. »We want to remove the fouling in stage 1 or early stage 2 – and always well before it becomes a problem in terms of hull performance and bio-security risk.«

Aside from cleaning or replacing the antifouling during dry-dockings, hulls and propellers may be cleaned occasionally in water while in service. However, at this stage fouling is already a major problem. In addition, manual cleaning by divers is no longer permitted in a number of ports. Many others are considering banning such activities. That does make following the International Maritime Organisation’s (IMO) biofouling guidelines difficult and is something that will need to be addressed if controls become mandatory.

A key aspect for a broader implementation of proactive cleaning technologies like this is the regulatory part in ports.

To encourage the regulatory development, Jotun initiated an »own« guideline. The intent is to provide input to ports and other jurisdictions facing requests for proactive in-water cleaning of ships underwater hull areas while in port or at anchorage. The authors want to address key points to consider, such as requirements and how delivery on these requirements is to be documented.

Piloting in more than 30 ports

Enström explains: »There is no harmonized regulation yet, it is a very diverse landscape. An important first step is to bring technical guidelines into the maritime public. We have developed such a guideline on our own – in a way a bottom-up-approach – that needs to be aligned. We invite the different stakeholders to provide their knowhow to our document.« A global guideline is needed. However, he adds, one challenge is that there is a lack of a global body for port regulation. IMO has an important role to play, also BIMCO is active.

Over the last three years the experts have been piloting the solution at more than 30 ports worldwide, including ports in Europe including Germany, West & East coast in the US, Australia and New Zeeland, Singapore, Japan, Korea and South Africa. This has been done in close dialogue with ports and environmental authorities with the aim to establish a »commonly agreed upon guideline«. Enström and his colleagues have so far got »very positive feedback from various ports.« However, they need to talk to every single port before they start operating there. It is a complex situation, sometimes discussions to more than body in a port are needed.

Permissions are still granted on a case by case basis. So far there is only one port where the HullSkater has failed to get permission.

This topic was discussed at the high-level expert conference PortPIC 2020 in Hamburg.